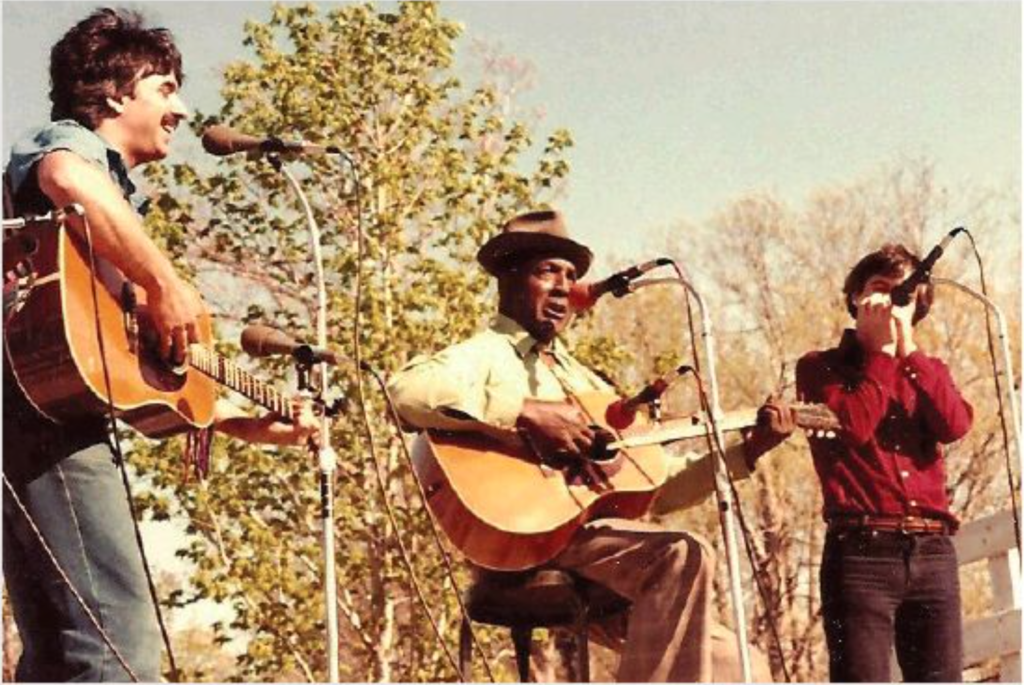

Richard Sleigh of Boalsburg has made a life of playing and teaching the harmonica and building custom harps. He’s shared the stage with symphony orchestras and musical giants – Bo Diddley and Taj Mahal, to name just a couple.

Sleigh, 69, is known the world over as a master harmonicist, but he traces his inspiration back to little Philipsburg, where he was born and raised and first introduced to the harmonica.

“My first harmonica was some kind of a Marine Band harmonica, the 10-hole Hohner Marine Band,” Sleigh recalls. “I had a great uncle in Philipsburg who played the old style, tongue-blocking harmonica. He played old tunes like the The Irish Washerwoman and ‘Way Down on the Suwannee River’ (Old Folks at Home), stuff like that, and also the train imitations, which are a big part of the blues harmonica history.

“The Central Hotel building in the middle of Philipsburg, Second and Pine, in the summertime, he would be up in the third floor with the window open,” Sleigh continues. “He would attract a crowd. He wouldn’t even know – he’d just be sitting in a rocking chair, and I’d be sitting there, and all of a sudden, you’d hear this applause coming up from the street, and you’d realize we had an audience.”

Sleigh didn’t take music lessons from his Great Uncle Bill but says the childhood experience of listening to the harmonica “just got in in my ear.”

‘I just went nuts over there’

Sleigh played guitar in a garage band in high school and was still a guitarist when he was an art student at the Penn State Altoona campus. He started listening to Bob Dylan and the Beatles, whose earlier music incorporated a lot of harmonica.

“There were so many great guitar players around that I couldn’t get into a jam edgewise at a party and have anything interesting to say,” says Sleigh. “And that’s also when I discovered Sonny Terry and Little Walter and Big Walter and Sonny Boy Williamson and Muddy Waters and all of those Chicago blues players who played harmonica.”

During his 1970 spring term at the campus, Sleigh says, “I just went nuts over there. I started playing the harmonica all the time, and it’s all I wanted to do. School was just basically a nuisance. I would buy every record I could find that had a harmonica on it and try to do whatever they were doing on the record.”

At first, Sleigh thought he’d stumbled on an instrument that would be much more affordable than a guitar. But then, he learned two things:

“One, the harmonica comes in different keys, and if you don’t have all the keys, chances are whatever it is you’re listening to, you’re not going to have the right harmonica,” Sleigh says. “And the other thing is that they wear out. So you either have to retune them or buy a new one.”

Sleigh started accumulating harmonicas in boxes early on.

“It turned out the harmonica was possibly more expensive than playing the guitar if you played it all the time, because you kept having to deal with replacing the instruments,” Sleigh explains. “And that’s when I started tearing them apart and figuring out how they worked and started tuning them and making my first thousand mistakes dealing with making harmonicas last longer.”

The verge of invention

Sleigh mainly plays a diatonic or blues harmonica with 20 reeds in it. Ten reeds are activated when you draw through the instrument – the draw notes – and the other 10 are activated when you blow through the instrument – the blow notes.

“It is set up around a major scale, so to be able to play in any key, it’s best to have a complete set of 12 harmonicas – one in each key,” says Sleigh.

There are other variations of harmonicas – different octaves, alternative tunings, and so forth.

“You really can go crazy collecting all kinds of variations,” Sleigh says. “But they still fit in a lot smaller space than a guitar collection. You can always carry one with you in your pocket.”

The harmonica has a free reed in it that vibrates when you activate it with your breath. The reeds are tuned to different pitches, but you can also create other notes from the combination of the reeds in any given chamber to fill in some of the notes that are missing in the major scale.

“It’s called ‘bending notes,’ and it’s one of the things that gives the blues harmonica its characteristic sound,” says Sleigh. “It has a very human vocal quality to it. That is one of the more mysterious parts of the instrument, because you can bend these notes, and you can get most of the other notes.”

In the mid-1980s, Sleigh commenced a journey to prototype and patent a harmonica that would enable the player to bend the notes on the blow notes as well as on the draw notes.

Unbeknownst to Sleigh, several other harmonica players were also working on an ultimate bending diatonic harmonica at the same time he was, and someone else ultimately came away with the patent.

“I think we should start a support group for all of the people who were working on this idea, but didn’t get the patent,” Sleigh jokes.

Nonetheless, through his invention process, Sleigh formed a close connection with Joe Filisko in Illinois, whom Sleigh describes as a “real pioneer in that whole area of customizing and fine-tuning instruments.” Sleigh credits Filisko with giving him the idea of making a living out of servicing harmonicas.

“Since I already had a lot of the tools and obviously knew what I was doing and could play really well, [Joe] got me involved, and that’s how the business got started, when we moved to Philipsburg, and I started working on that,” Sleigh recalls. “It wasn’t a get-rich-quick scheme. It was a lot of figuring stuff out. At that point, not a lot of people even understood how the instrument really worked. Since I had been working on the instrument, I had a much better idea of how the innards of the harmonica worked, and we started working on ways to make them high-performance.”

Saving an icon

Around this same time, Sleigh and a band of other harmonica experts set out on a quest to save the beloved Hohner Marine Band harmonica.

“The Marine Band is the most iconic harmonica ever made,” Sleigh explains. “There have been more Marine Bands sold than any other harmonica, and it’s the one most of the classic blues recordings were made on, and it’s the one most blues guys, if they don’t play them, they started on them.”

In the ’80s, Hohner changed how it manufactured the instrument, and the slots in the reed plate became too big for the reed, creating compression problems.

“It was hard to find harmonicas that played as well as the old ones,” Sleigh says. “There were all these blues guys out on the road trying to find harmonicas that worked right. I’d fix them up and send them back, and people would go nuts and tell their friends, and I had just boxes and boxes of harmonicas at one point. I mean thousands. And it was just crazy.”

‘Doctors and lawyers and weekend warriors’

Sleigh now builds and fine-tunes custom harmonicas in his basement workshop in Boalsburg as a member of the prestigious Hohner Affiliated Customizer Program.

Just as with every hobby or profession, there is a community of people who are aware of the top personalities of the harmonica world.

“I became one of the people who became known as one of the pioneers of the custom harmonica, so when somebody gets the idea they want to get a high-end harmonica, I’m on the short list of people who can do that,” Sleigh says. “Without doing very much promotion, I’ve basically had people finding me over the last 25 years. And they’re everywhere. I’ve got customers all over the world. Over the past 25 years, that’s kept me from having to get a real job.”

Sleigh says his best customers are “doctors and lawyers and weekend warriors.”

“They’re like the people who play golf, and every time a new golf club comes out, they gotta go buy it,” says Sleigh. “So that kind of means, plus obsession, is really the people who keep this business going. A lot of the pros aren’t making enough to drop tons of money on top instruments. Since I can build my own harmonicas, I’m good to go.”

Building, performing, teaching

Sleigh has performed all over the place and is still a staple at local venues.

“Over the years, as a player, I’ve had the opportunity to do some really fun gigs,” Sleigh says.

One of Sleigh’s most memorable performances was playing with the Bridgeton Symphony Orchestra in New Jersey.

“That was amazing,” Sleigh says. “Because I’m right in the middle of the orchestra – right directly in front of the director. And so you’re immersed. If you’ve ever been right there in the middle of a symphony orchestra, the sound is overwhelming. I was terrified that I was going to blow the cue because I was so disoriented. It’s so different from practicing your part at home. But when the director gave me the down beat, I hit it, and he was happy with me, and that just felt like a million bucks.”

Sleigh also has fond memories of The Brickhouse, a State College tavern that closed in 1990.

“An amazing number of people played there in this little, tiny place,” Sleigh says. “I opened up for Bill Monroe, Taj Mahal, Maria Muldaur, Paul Gerimia.”

In addition to building custom harmonicas and performing on the instrument, Sleigh also offers private lessons and has recently begun an online harmonica school through the platform called “Teachable.”

To fellow creators just starting out, Sleigh advises “having real respect for your craft,” “creating a practice,” and “working on your craft even when you don’t feel like it.”

“Part of [my success] was being obsessed,” Sleigh says. “If you want to learn to play an instrument, then find a teacher who can give you something organized to practice, and then just take it one step at a time; then you start getting good, and then you start getting more inspired. Find a community that supports practice and other people who are using the internet to inspire each other to get better at their craft. That’s a great way to use the online resources.”

‘That collective buzz’

For Sleigh, playing the harmonica is akin to how Billy Elliot describes dancing in the film by the same name.

“It’s like electricity,” Sleigh says. “That’s what it’s like. It’s like this energy when everything clicks, and it comes together. It’s that flow state, that energy, that electricity, that feeling that time has stopped. When you experience that, you never forget it, and you want to do it again. And it’s worth all that time you spend building your craft. And practicing the scales and learning the songs and doing everything. And that’s why people like music, and they like to dance, because you lose yourself in the moment. And that’s really to me what it’s about – to be in the arts, or just to approach your life in creativity. You can be an ace car mechanic and go into that state. But there’s something about doing it in front of an audience where the energy of the audience amplifies it. That is incredible. And it’s that collective buzz.”

For more information about Richard Sleigh, visit hotrodharmonicas.com.

Teresa Mull is a freelance writer in Philipsburg. This story appears in the June 2021 issue of Town&Gown.