RIGA, LATVIA – A wall bearing the names of the 70,000 Latvian Jews who died in the Holocaust stretches the length of the courtyard of the Riga Ghetto and Latvian Holocaust Museum.

I make for the “F’s”: My paternal grandparents came from here. They left long before Hitler’s rise so I’m not looking for their names. But perhaps there are members of the extended family who stayed behind?

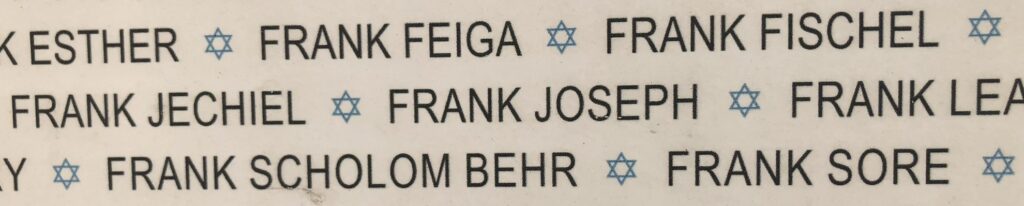

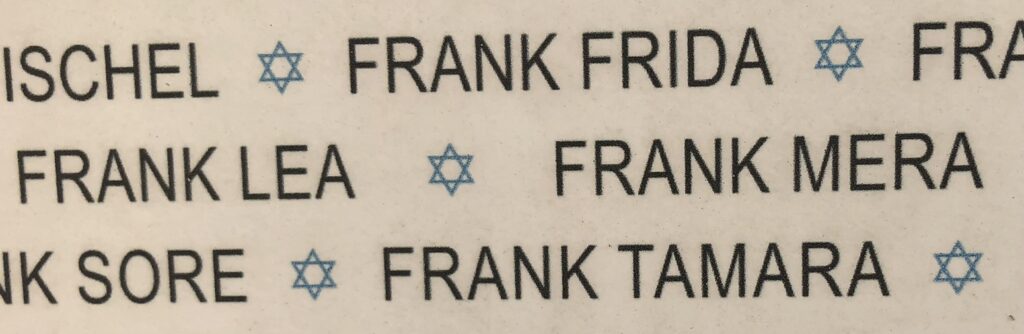

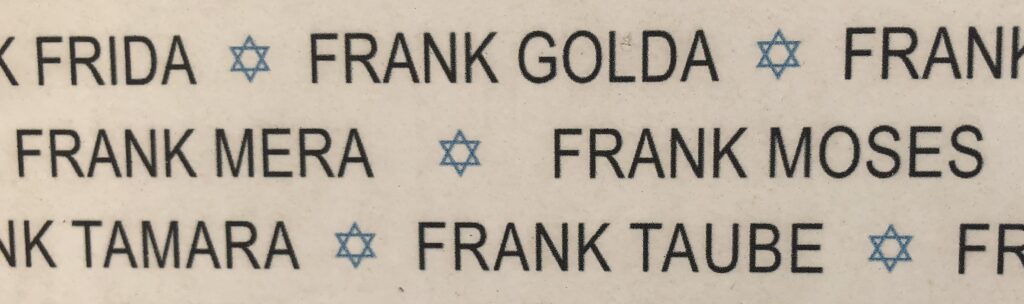

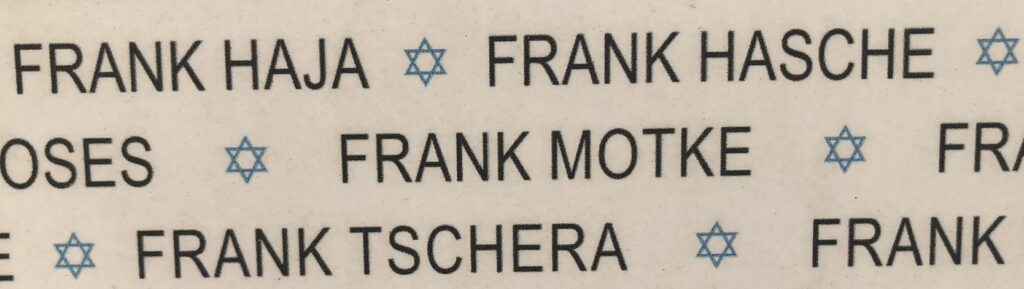

I’m surprised to see 29 Franks on the wall: Ary, Berl, Esther, Itzik, Itzik Leib, Scheina, Schmary, Feiga, Fischel, Jechiel, Joseph, Scholom, Sore, Frida, Lea, Mera, Tamara, Golda, Moses, Taube, Haja, Hasche, Motke, Tschera, Reisa, Hesja, Ilja…

Are any of them great aunts or uncles or cousins who-knows-how-many-times removed? Were my relatives among those taken to the forest and shot, worked or starved to death, hanged in the Jewish ghetto or sent to their doom in one of the camps? No idea.

Then there are these two: Wulf and Rivka – my grandparents’ namesakes, but not my grandparents, obviously. Still, it freezes me to see Wulf Frank and Rivka Frank on that wall, just as it once froze me to see a plaque that read “Mr. and Mrs. Frank’s Bedroom” in the Anne Frank house in Amsterdam. Mr. and Mrs. Frank were my parents, not Anne Frank’s. Their bedroom was on Long Island, not in the Netherlands.

It is of course true that I owe my life to Wulf and Rivka’s decision to come to America, and tempting to say that their departure saved my dad from the Holocaust. But assuming that every act of conception produces a unique human being, if Wulf and Rivka had my dad in Latvia instead of New York, he would have been someone else. And that someone else wouldn’t have met my mom, who would also have been someone else if her parents had stayed in Poland.

Still, the sense that Latvia is one of my ancestral homes resonates. It took being invited to a wedding in Sweden to get me here. (We figured as long as we were in the neighborhood, we’d visit Finland, Estonia and Latvia.)

The Baltics aren’t a top-of-the-mind destination for American travelers, but they offer a lot to see and think about. The guidebooks rightly tout the Old Towns in the capitals — Tallinn in Estonia and Riga in Latvia – as fairylands of cobblestone streets, 500-year-old buildings and towering spires. (A few too many tour groups for my taste, but oh well.)

Riga also has a killer Art Nouveau district: delightfully and in some cases preposterously ornate building fronts from the turn of the 20th century.

More compelling for me, though, is the history of these places, and the telling of the history in two superb museums, the Museum of the Occupation in Riga and the Vabamu Museum of Occupations and Freedom in Tallinn.

In excruciating detail, these museums remind us that life in the Baltics was an unending nightmare for most of the 20th century. There was Soviet oppression between the world wars, being kicked back and forth between the Soviets and the Nazis during World War II, then more Soviet oppression from World War II until independence in 1991.

Looking at the prosperous places these cities have become, I wonder if the young people appreciate how wide the gap is between their lives and the lives of their parents and grandparents. I wonder if the parents and grandparents, with Russia forever breathing down their necks, fret that they’re living on borrowed time. No one has watched Putin’s invasion of Ukraine more uneasily than our friends in the Baltics.

On a train between Riga and the coast, I ask a recent high school graduate if his parents ever talk about the bad old days of privations, beatings, deportations to Siberia. They don’t. I ask if he ever asks them about those days. He doesn’t.

I urge him to inquire, just as I urge my students to question the elders in their families.

I do this as one who knows woefully little about his own family history and no longer has anyone he can ask. (Pre-Holocaust records of Jewish communities can be hard to come by.)

Wulf and Rivka were long gone by the time I was old enough to understand what it meant to come from “the old country.” So was Morris Berg, my maternal grandfather.

But for a long time, there were my parents. There were aunts and uncles. Above all, there was Grandma — Yetta Berg, my mom’s mom, who lived well into my adulthood.

I know nothing about Grandma’s life in Poland or why she and Morris left. It never occurred to me to ask. She was just Grandma. It never occurred to me that she had a life before she became Grandma – understandable for a little kid, inexcusable for a journalist and folklorist.

I swam in the Baltic Sea while I was in Latvia. It soothed me to imagine that I might not be the first member of my family to splash around in those waters.

But I’ll never know.