PRESTON, IDAHO – Just north of Preston, the town where “Napoleon Dynamite” was filmed, past Polar Bear Burgers and Shakes, past the Pop’n Pins bowling alley, past The Hangout, the Jiu Jitsu studio, Big J Burgers and the Spit Shine car wash, is a terrible, peaceful place – site of the worst massacre of native people in the history of the West.

I’m here on a tour led by Darren Parry, a member of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation. Parry’s ancestors were killed in the Bear River Massacre, which is the title of the book he has written about what took place here.

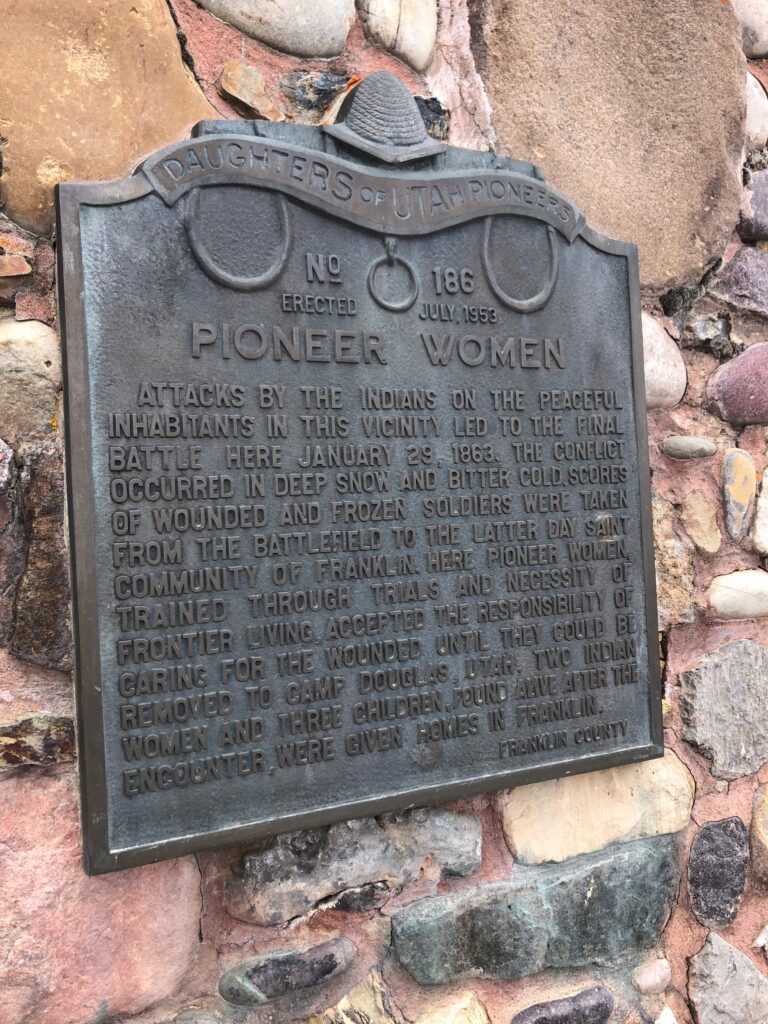

Our first stop is the historic marker placed by the Daughters of Utah Pioneers in 1953. Here’s how it begins:

Attacks by the Indians on the peaceful inhabitants in this vicinity led to the final battle here January 29, 1863.

The rest of the little narrative focuses on the care for the wounded soldiers. And then at the end it tells us that “two Indian women and three children, found alive after the encounter, were given homes in Franklin.”

I love that word “encounter.” The word “battle” doesn’t do justice to what took place, either.

U.S. Army soldiers attacked a Shoshone village that winter morning. The men fought back but were soon overwhelmed.

“It may have started as a battle,” Parry says, “but after a half-hour it became something much worse.”

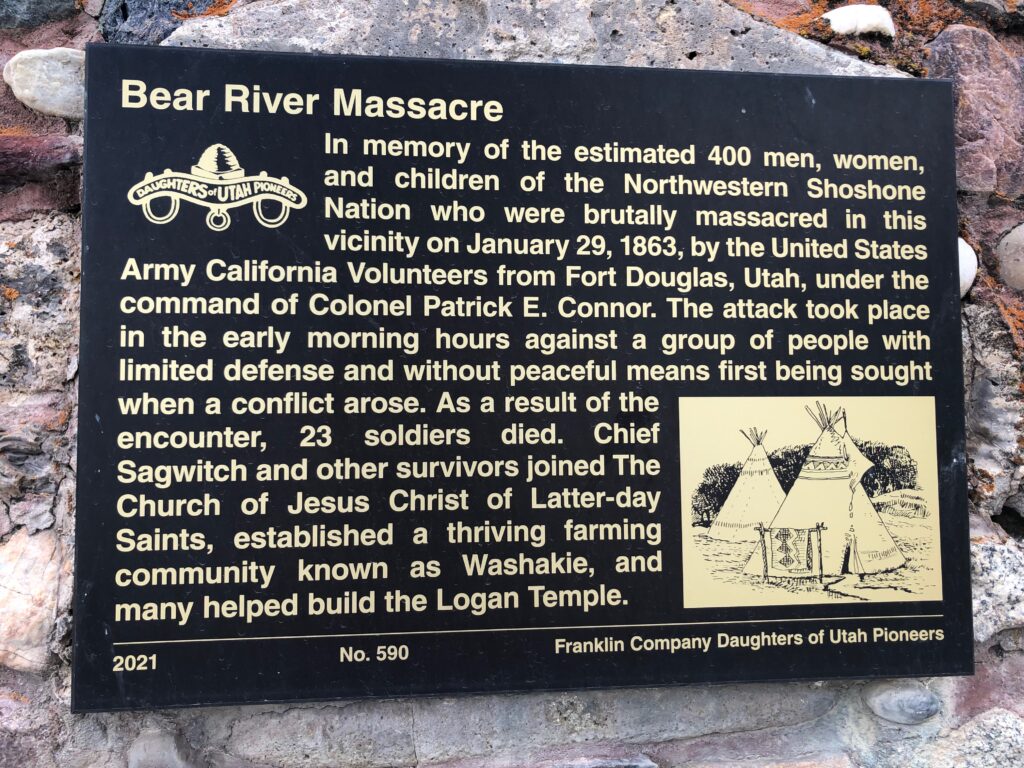

About 400 Shoshone men, women and children were killed.

The obvious question: Now that we live in slightly more enlightened times, why not ask the DUP to replace their plaque with one that better reflects what really happened?

Parry’s answer: “It’s so bad I want to keep it as a teaching tool.”

Instead of replacing the plaque, Parry wrote the text of another one that he got the DUP to affix to the back side of the teepee-topped monument. The new one, installed in 2021, calls the thing by its true name and tells us the body count, including the 23 soldiers who died.

Also on the site of the monument is the Honor Tree, adorned with memorials left by visitors. One of the objects is a mirror. A fourth grader on one of Parry’s school tours interpreted it: “To remind us that we did this,” she said.

From the highway marker, it’s a short drive up an unpaved road that gets us as close to the site of the massacre as one can get. The land slopes down to the river, called the Bia Ogoi (Big River) by the Shoshone. Across the valley lie the Cache Mountains, still snowcapped. As we gaze at the site, cloud shadows sweep across it.

The soldiers chased the people from their lodges to the river. Those who made it that far without being shot jumped in. Most froze. Parry told us about one new mother, wounded seven times, who drowned her own baby to survive.

Parry heard the stories from his grandmother, Mae Timbimboo Parry. Her grandfather – Parry’s great-great grandfather — played dead until the soldiers went away. The leader of the raiding party, Patrick Connor of the U.S. Army California Volunteers, was promoted from colonel to brigadier general.

Amazingly, Parry says he loves coming out here. “It’s more of a story of survival for me,” he says. This is not a bitter man.

The Shoshone have reacquired the land where the massacre took place. Parry is raising money for an interpretive center, an amphitheater, a trail and a parking lot.

In the meantime, when he isn’t leading tours, he likes to just sit and look out, as he used to do with his grandmother when she told him her stories, partly in English and partly in Shoshone. (Parry says there are six speakers of Shoshone left. “I make six-and-a-half.”)

Sometimes he comes out here with a drum and sings.

Plans for the site, some of which are already under way, also include healing the land: removing the water-sucking olive trees that aren’t native to the place and reintroducing trout and beaver to the stream that feeds the river.

Before they started, Parry says, pointing to Battle Creek (the Shoshone called it Beaver Creek), “that was chocolate milk.” The goal is to get the water to run clear, and for it to flow southward into the Great Salt Lake, which needs all the replenishing it can get.

Our tour was arranged by the organizers of the conference I’m attending at Utah State University, just over the state line in Logan. I thought about staying back at the hotel and writing this column on some other topic. I’m glad I didn’t.

Just before we get back on the bus to head back to campus, a bald eagle soars over the massacre site, crosses the river and flies off toward the mountains.

When we drop Darren Parry off by his car, he thanks us.