Some students take a gap year after high school. Irvin Moore took a gap half-century.

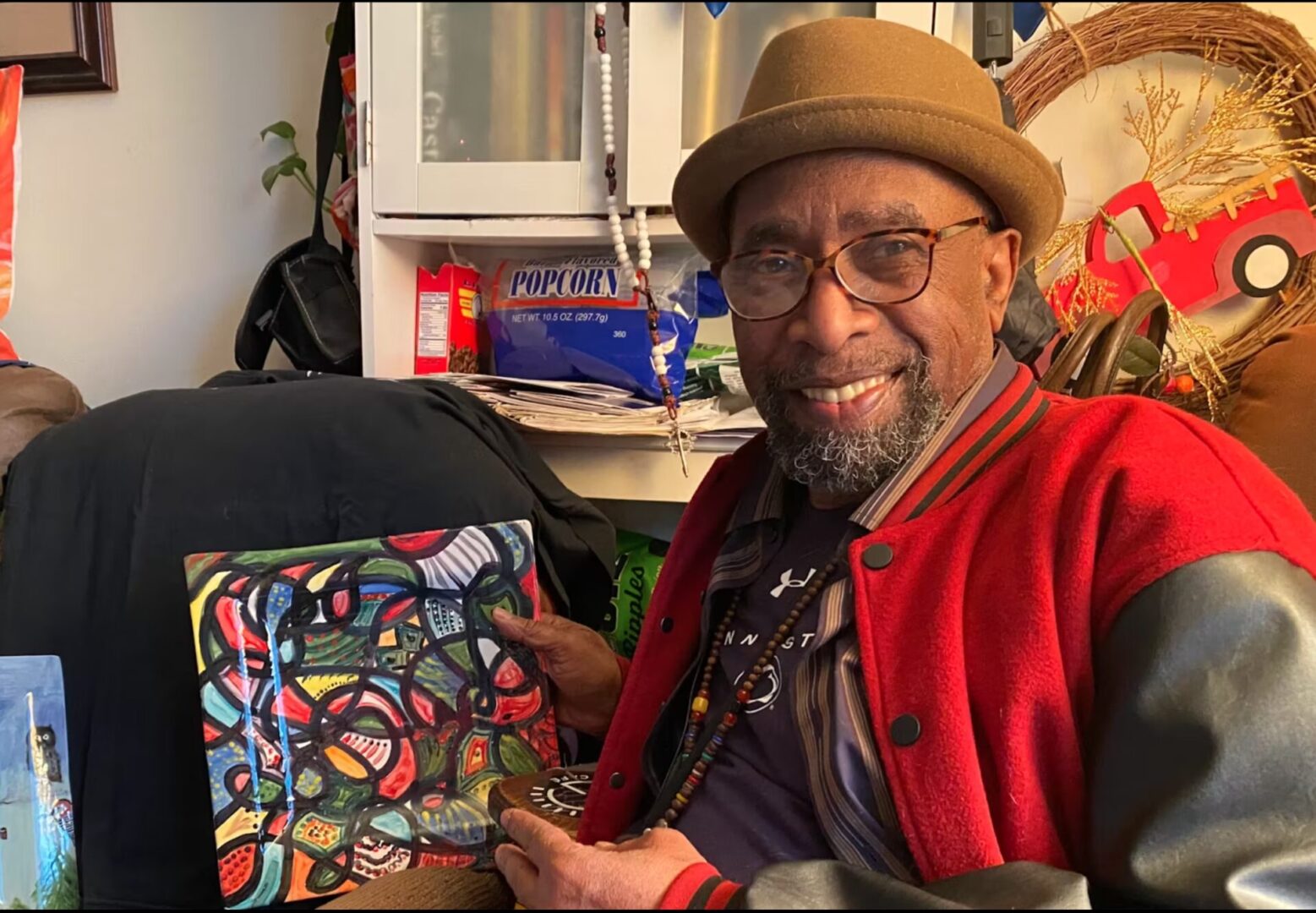

It wasn’t by choice. Moore went to prison on a murder charge at the age when many kids graduate from college. He walked out 52 years later, not just older, but infinitely wiser. Next week, at the age of 78, he’ll be a Penn State student. His goal: to graduate at 80.

It’s attainable because Moore isn’t entering as a freshman. After completing a high school graduate equivalency degree, he earned two associate degrees while an inmate.

But that was a while ago. Friends and academic advisers at Penn State counseled him to ease back into academic life by taking one course this fall. He had planned to take five.

What they don’t realize, he told me over an outdoor lunch on campus, is that he’s been studying his whole adult life. This is the guy who had accumulated 500 books in his prison cell by the time they let him out.

Still, he conceded that five courses might be a bit much. He’s now enrolled in two classes this semester and if all goes well, he’ll take on a heavier load in the spring.

As for what he’ll study, it’s a no-brainer: He’ll be one of about 200 students in the Rehabilitation and Human Services (RHS) major in the College of Education.

One course that’s right in his wheelhouse is Rehabilitation Corrections. Among the topics addressed in the class, according to the Undergraduate Bulletin, are reentry services for offenders, which is exactly what Irvin has been doing since he began working for the College of Education’s Restorative Justice Initiative two years ago.

Given his criminal record, Irvin’s acceptance by Penn State wasn’t a slam dunk. A hold was put on his application while the university determined that he wouldn’t pose a threat to other students.

“Did I panic?” he said. After everything he endured in prison – beatings, hosings, being “locked in a box,” he said, “I’m never going to panic about anything in life. Every day I wake up, I say, ‘Lord, you’ve given me another one.’”

OK, I said to him, so it’s the first day of class and you have to decide where to sit. Are you going to be a front-row guy, head for the anonymous middle, or hide in the back?

My guess was front row. I was right. As a stuttering elementary schooler, Irvin tried to sit in the back behind the tallest kid in the class so he wouldn’t be called on.

Not surprisingly, the stutter caused him to be teased and the teasing led to fights.

“So I learned to speak,” he said.

How? By reading to and telling stories to his younger brothers and sisters and nieces and nephews. Sometimes he read them the ingredients listed on a cereal box.

It worked. These days, Irvin is more than a competent speaker. He’s eloquent. And he gets lots of practice: He has given more than 50 talks at conferences, prisons and Penn State classes in the past couple of years.

It occurred to me that the problem now won’t be that he’ll sit in the back of the room and try to be invisible but that he’ll have so much to say that he’ll dominate the discussion and intimidate his classmates, who will be young enough to be his grandkids, into silence.

Irvin’s not worried about any of that. When he was young, people told him he acted like he knew everything. Prison cured him of that. He’s in school to learn, he insists, not teach. But I have a feeling his classmates are going to benefit from what he knows.

Deirdre O’Sullivan, the professor in the College of Education who runs the RHS program, has the same feeling.

“He’s bringing in expertise,” she said. “Whoever is teaching his classes will appreciate that and incorporate that.”

A few days after we spoke, I ran into Irvin again, this time on a bench outside the Chambers Building with his dog Kora. My friend Samar Farage was passing by also. When I told her Irvin was going to be a student in the fall, she encouraged him to take one of her sociology classes.

“He would be a big star in my class,” she said.

“I’ll just be Irvin,” he replied.

I tried to find out if Irvin is going to be the oldest student in Penn State history, and came up empty. He’s got to be one of the oldest.

Any trepidation about going back to school, I asked him.

“I’m overjoyed,” he said.

And what about after the B.A.? M.A.? Ph.D.?

“Quite possible,” he said. “They called me Professor on the inside.”

In prison, he means. Don’t be surprised if everyone winds up calling him Professor on the outside.