This story appears in the May 2021 issue of Town&Gown.

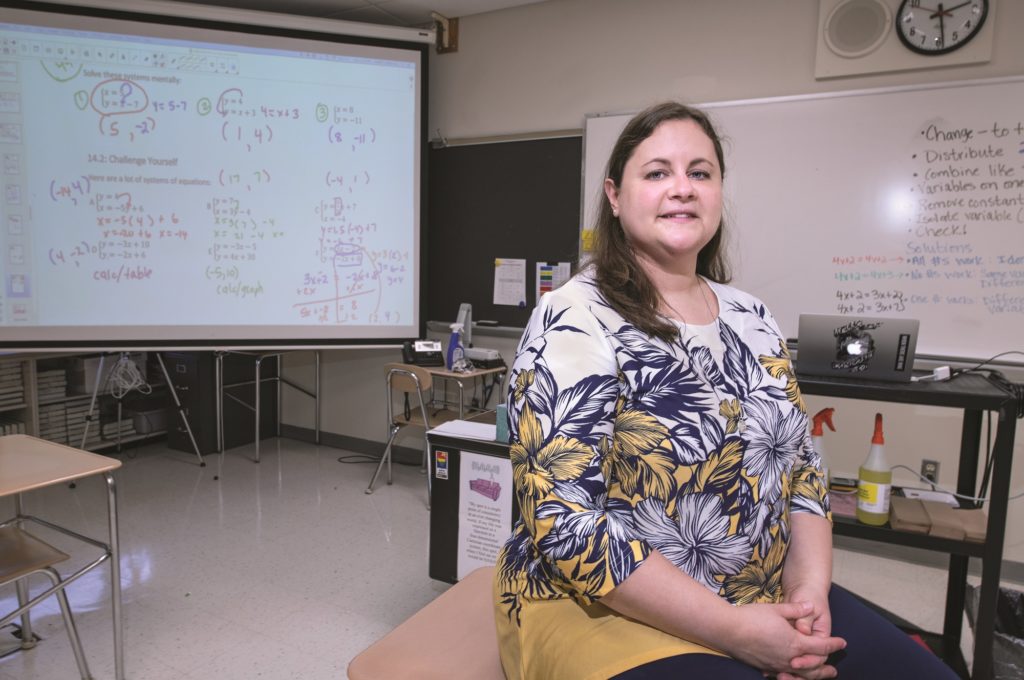

In the fall, Mount Nittany Middle School math teacher Rebecca Henry spent her nights and weekends retooling the algebra lessons she had taught for years, so they could be available to online learners at home.

She also had to juggle to implement Canvas, a new online course management system, for her classes, while simultaneously teaching and keeping up with grading.

“I’ve never been so tired and burned out in my life,” says Henry, who had to make the adjustments because of major changes to her classroom with coronavirus protocols. “It was hard to stop working. I knew if I didn’t keep going, it would just pile up.”

A dozen teachers interviewed for this article, including Henry, are nearing the end of what they call the most difficult school year of their careers. The COVID-19 pandemic brought about drastic changes to the way they do their jobs, as they were forced to teach students in their classrooms and online at the same time, while following social distancing and other health and safety guidelines.

What has emerged, though, is a portrait of resilient teachers. Through interviews, teachers detailed how they responded to the challenges with new teaching strategies and a lot of sharing with their co-workers to try to educate students and build community among them, no matter where they are learning.

“It has been one big emotional roller-coaster,” says Aaron Chamberlain, a math teacher at State College Area High School who occasionally taught at home while having to care for his two young children. “Life threw all it had at us in one year, and look, we are still going. We are a resilient community, we are a strong community, we are a helping community, and we are a caring community.”

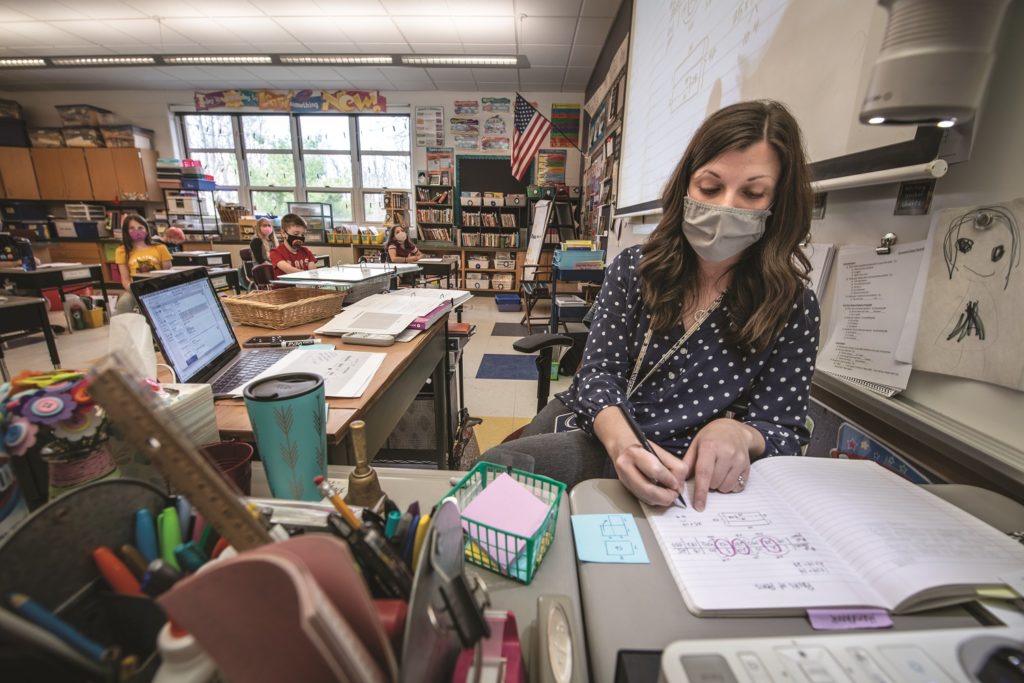

To start this school year, local districts required strict adherence to health and safety protocols: Students and teachers must be masked except during breaks. Students’ desks were spaced 6 feet apart. Classrooms, cafeterias, and buildings all had capacity limits that reduced the number of students who could be together.

The districts also offered several attendance options to offset the capacity limits and provide an alternative for parents who did not want to send their children to school. Students could attend in person or they could attend remotely by logging into their teachers’ webcam feeds. Some districts required alternating between in-person and at-home days.

Working out the kinks

Laurie Pagnotto, a kindergarten teacher at State College Area’s Spring Creek Elementary School, started the year with 18 students in her classroom and five online. Creating and using a completely different classroom for such young students didn’t seem sustainable. For instance, her reading corner and carpet were gone. Tables were replaced by individual desks.

“The environment looks a lot different from what it was,” Pagnotto says. “How could I manage this environment, but still make it kid-friendly and exciting for kindergartners? That was always at the forefront of my mind – how to motivate them, inspire them to want to learn, not being inhibited by the environment we’re in.”

Pagnotto credits her student teacher for helping to bring some calm to the chaos at the beginning. Pagnotto would lead a group lesson for all students, and then her student teacher worked with the online learners while she and her aide worked with those in the room.

“That was truly a challenge day-to-day, and by the end of the day we were exhausted,” Pagnotto says. “My student teacher and I would regroup and think about how to do it each day.

“Finally, we’ve been here long enough and worked through all of the kinks. The kids are having fun now. You can see them smiling. They’re just like a normal class, but 6 feet apart and with a mask.”

Jaymie Ramey, a first-grade teacher at Easterly Parkway Elementary School, is teaching a fully online classroom after starting with nine in-person and 10 remote learners. A teacher for 16 years, she says she never had to teach online and found the hybrid format difficult.

“One of the most important things in teaching is building that connection with kids,” she says. “It was really different to not give a hug to a kid who was nervous or to give a high-five when someone walked in. How do we build connections with students so they know they are safe and cared for at school?”

When the district nixed the hybrid format for K-2 students in October by creating new classes for the remote learners, Ramey opted to teach online. She had 26 students, and they’ve been meeting virtually through Google Meet.

Ramey says she still must work nights and weekends, and while it’s tiring, she’s seen it pay off.

The students like having personalized virtual backgrounds, she says. They’ve gotten used to the app Seesaw, which houses their activities. For math, she uses online games, and students are excelling at sharing their screens in breakout rooms to talk one-on-one.

“Having such a large group and such a young age has been very interesting, difficult and humbling, but it also has been a really eye-opening experience,” Ramey says. “These kids are more resilient than any of the adults.”

Madison Gallaher, a third-grade teacher at Penns Valley Elementary School in the Penns Valley Area School District, says the protocols that limited her students from working closely together were the biggest hurdles to overcome. Her classroom is also hybrid, with most of the students attending in person.

“Collaboration and cooperation are such a huge part of learning, and it’s been very different considering the fact the kids are physically spaced out all day,” says Gallaher, who is in her third year. “It’s very hard to set aside teaching strategies that I know are effective because of the space we have to adhere to this year.”

There are even challenges that seem small but loom large: She says students don’t always recognize she’s talking because they can’t see her mouth moving under her facemask.

Gallaher says she has had to make adjustments for things she never considered would be issues. For instance, she bought a pair of wireless earbuds so she could freely move around the room while hearing the audio from her online students, who were connected via an iPad.

Early childhood educators also saw their normal routines upended by the pandemic.

Amber Panetta, who teaches 3-year-olds at Our Lady of Victory Preschool, says the increased cleaning and safety were the biggest changes she had to accommodate in the day.

Panetta says she had a unit for her students on handwashing and she has timers by the sink in her room so the children know how long to wash. Teachers had to spray surfaces like toys, tables, handrails, and door knobs, among others. She also did temperature checks and a health questionnaire screen each morning when the preschoolers were dropped off.

“We just adapt, pivot,” Panetta says. “Whatever’s thrown at us, we figure out a way to make it work.”

Dawn Lorenz, the director of the OLV Preschool, commends her staff.

“They’re encouraging great behaviors, and they’re still providing quality education,” she says. “How they’re doing that in the midst of this, I have no idea.”

Google Meet and YouTube

At the secondary level, teachers have found themselves teaching with more online learners than in the elementary grades.

Henry, the Mount Nittany Middle School math teacher, says the mixed instructional mode presented challenges for her subject area. Her students are solving equations, and she needs to see the work they do to solve them. Just seeing answers won’t help.

She’s using a free online math program called Desmos that both sets of students can work in. It has a lot of functions – she can make slideshows and whiteboards, and there’s a sketching tool for students, among others. And she can see her students’ individual progress in real time to provide feedback, alleviating her original concern.

Fall semester was “the hardest semester of teaching in 23 years that I have had,” Henry says. Nevertheless, she says her students made the best of it.

“My fall kids got really good at just chiming in, talking as if they were in the building with the rest of the kids,” Henry says. “We got really adept at using the chat feature in Google Meet. They would have conversations. Even with this craziness of the fall semester, I was still able to form a lot of connections with my kids.

“That was pleasantly surprising to have that community feel.”

Like Henry, Park Forest Middle School teacher Heath Stout had to be innovative to teach his curriculum, seventh-grade general science. Initially, the notion of not having hands-on labs for students created “all-out panic.”

Stout and his grade-level science colleagues created about 80 short videos on YouTube that showed them demonstrating the labs the students couldn’t do because of distancing and strict contact protocols.

This approach still works, he says. By watching the videos, the students think like scientists, exploring and testing hypotheses to find their answers. He admits it’s made the students more passive, but it still drives home the point.

“To get the kids to be engaged, you have to hear what they’re thinking,” Stout says.

Stout says his colleagues’ lab videos “would have never taken place” if they hadn’t had time to work together in the fall. Stout, who is a union representative for his building, says teachers hope there’s an understanding of how much went toward pulling off everything they did.

‘Was it valued?’

“I think everybody has this big question – was it valued?” he says. “Did people value what we did this year? That’s really weighing on teachers.”

Larry Fry, a sixth-grade social studies teacher at Bellefonte Area Middle School, can relate. He says teachers in the Bellefonte Area School District had to quickly learn how to use various technology applications in their classrooms, and then they had to figure out how to use it so the students in class and tuning in online had the same experience.

“We’re basically running two classrooms this year,” he says. “Every day is a new adventure. Just when you think you’ve seen it or all or done it all, something new comes along. You do your best job.”

Brian Ishler, the principal at Mount Nittany Middle School, says administrators understand how hard it’s been to teach on two fronts.

“The toughest piece is they have kids in person and they have remote kids. It’s hard to choose who to focus on,” Ishler says. “If the kid is in front of you, you can read their body language and read their face. Teachers can tell. It’s tough to tell over Zoom or Google Meet.”

Ishler also says he understands the roller-coaster of emotions they’ve experienced as State College schools switched from in-school learning to fully remote learning a few times in the fall, as the number of local COVID cases surged.

“That was hard on them just not knowing how they’re teaching next week,” he says. “The teachers and students have a routine, a set schedule that they’re used to.”

Shai McGowan, the president of the 630-member State College Area Educators Association, says hybrid teaching has been so challenging because teachers were never trained this way. They had to learn it and apply it on the fly. For some, they feel like they can’t do enough and have failed their students.

“Trying to build that community when you have students in all models of teaching is tough,” McGowan says. “I think that is one of the struggles that good teachers struggle with. They pride themselves on that welcoming, supportive community within that classroom.”

Teachers’ morale took a beating and they have struggled with their mental health, too, McGowan says. She’s encouraged them not to compare this to previous years.

“When teachers are so used to being really good teachers, and all of the sudden they can’t keep that same level, they struggle with that,” she says. “Our teachers are exhausted. They want normalcy.

“Our teachers will continue to always put the student first. That’s what we do. They’re definitely resilient.”

The State College district is expecting to spend more than $4 million to operate as it has under its health and safety guidelines, says Chris Rosenblum, a spokesman for the district. He says $3 million of the costs are covered by federal stimulus funding.

The accommodations include staffing, equipment, and supplies. For instance, the cost to hire staff to create dedicated K-2 remote classrooms was $1 million. The district purchased resources to help teachers facilitate learning, like subscriptions for Seesaw and GoGuardian, a remote-learning monitoring tool, and professional development videos on hybrid teaching.

The district purchased personal protective equipment for all staff; monitors, tablets and other devices for remote learning; and air purifiers, Plexiglas dividers, and humidifiers for sanitation and safety, Rosenblum says.

Parents are also taking note of the year teachers have had.

Pam Shellenberger praises her twin sons’ fourth-grade teacher for her resourcefulness on a day in December when the area saw a foot of snow, but school went on in remote-learning mode. The teacher, Michele White, at Park Forest Elementary School, and her fourth-grade team planned activities for their students to tie in the snow day. For instance, they tailored writing activities to a how-to piece in the snow, such as building a snowman or making a snow angel.

“We knew that we had to provide instruction, and we wanted it to be engaging and meaningful and also deliver it in a way that the kids could enjoy the weather and being a kid,” White says. “We designed a couple of activities to capitalize on some of those moments.”

Shellenberger appreciates the consideration for the children.

“It’s just another thing added on their plate that they have to be creative about,” Shellenberger says. “She nailed it. It was awesome. The kids didn’t feel that they missed out.”

Karen Styers, a fifth-grade teacher at Mount Nittany Elementary, says she and her colleagues also have been working hard to make sure students don’t feel they’re missing out in the face of the challenges.

From Day 1, she set out to establish a strong presence for her remote learners. She has a 41-inch smart TV screen among the rows of desks to display the remote learners’ feeds to their classmates.

“There’s a lot of positivity that’s just naturally in the air,” she says. “We forgot about the camera being in here after a few days. We don’t think of them as distance learners.”

Styers says she is proud of her students’ behavior, too.

“Behavior is learned, and what these students have learned is this idea that resilience moves people forward and keeps us hopeful,” she says. “They see they have those personality traits that can build resilience. You build the strongest resilience when you have the challenges that are the biggest.”

The State High ninth-graders in Rachael Borden’s English class in the first half of the year embodied resilience. They surprised her with a bunch of touching messages they held up in front of their webcams on the last day of class in January.

Borden says she didn’t realize what was happening at first.

“We love you, Ms. Borden,” said one. “You made English less bad,” said another.

The gesture was a sweet send-off for Borden, a second-year teacher. It was also validation that, despite the challenges of teaching and learning during a global pandemic, a teacher made such an impression on them.

“I think the community that we all built together was just so meaningful to them because they needed people in their lives this year,” she says. “That was a good confirmation that things went well.”

Mike Dawson is a freelance writer who lives in College Township. His wife is a teacher in the Penns Valley Area School District.