He’s certainly not the principal figure in the development of Penn State’s wrestling dynasty. That, of course, would be Coach Cael Sanderson. He’s also not the most dramatic contributor to our Sanderson-era memories. That would be one of the Nittany Lions’ superstar wrestlers like Ed Ruth, David Taylor, Zain Retherford, Jason Nolf or Bo Nickal.

But Ira Lubert — a 1970s heavyweight and loyal Penn State alum — has certainly played a major role in the building of a Happy Valley dynasty.

Rumors to the contrary, Lubert did not make a large gift to Penn State to help in the hiring of Sanderson. “People said that I wrote a big check to attract Cael,” says Lubert. “That was totally untrue. There was a lot of social media stuff that said Cael got a tremendous increase in salary to come here. That’s not true. He got a very modest increase in that first contract.”

But yes, Lubert did participate in Sanderson’s recruiting through non-monetary means—and as a result, he helped make State College the current capital of collegiate wrestling. And here’s the thing that impresses me. During his wrestling days at Penn State, Lubert spent more time on Rec Hall’s bleachers than on the competition mat. Many athletes with that experience would whine about their misfortune; Ira became an MVP as a Penn State alum. He’s made huge gifts from his wallet, his schedule book and his heart.

As I see it, without the Lubert legacy there might never have been a Sanderson supremacy. So if you’re looking for someone other than Cael to thank for seven NCAA team titles in the last eight years, here’s my suggestion. Consider Ira Mark Lubert—business leader, philanthropist, member of the Penn State Board of Trustees and a self-proclaimed failure in collegiate athletics.

* * *

The old wrestling room in Rec Hall had never seen anything like this. Teammates and rivals Dave Joyner and Ira Lubert had often competed head-to-head as each sought to earn Penn State’s heavyweight position. But those matches usually took “only” one or two overtimes.

This bout in 1971, however, lasted interminably longer — to the delight of the hundreds of fans who filled the workout area or looked through small hallway windows. Everyone watched silently, because of the growing drama and because Coach Bill Koll forbade anyone to root for one Lion over another.

It didn’t end until the two had battled for a whopping 29 minutes — eight minutes of regulation plus seven overtimes of three minutes each. Lubert finally became impatient for victory and attempted a two-point reversal rather than employing his reliable standup for a one-point escape. Joyner thwarted the reversal and maintained his heavyweight spot in the lineup by a razor-thin margin.

“They were two immovable forces,” says Andy Matter, Lubert’s freshman year roommate in Mifflin Hall and a two-year national champ for Penn State.

“We were exhausted,” recalls Joyner, also an All-American football player for Coach Joe Paterno. “I think Ira lost 10 pounds and I lost 12 pounds. I know we lost more than 20 between the two of us.”

“Twenty-nine minutes of wrestling is unfathomable,” says Lubert. “I was totally exhausted and dejected that I didn’t achieve the goal.”

The goal? Well, of course, Ira wanted to win the varsity position. But his real goal was to capture a national championship. Given that he had won the New Jersey high school title with a rare blend of size and quickness, that wasn’t some kind of “Crazy Ira” notion. But it seemed that the multi-talented Joyner always stood in Lubert’s way. Indeed, the State College native captured second place at the 1971 NCAA tournament. Only when Joyner was focused on football did Lubert get to display his own considerable talent.

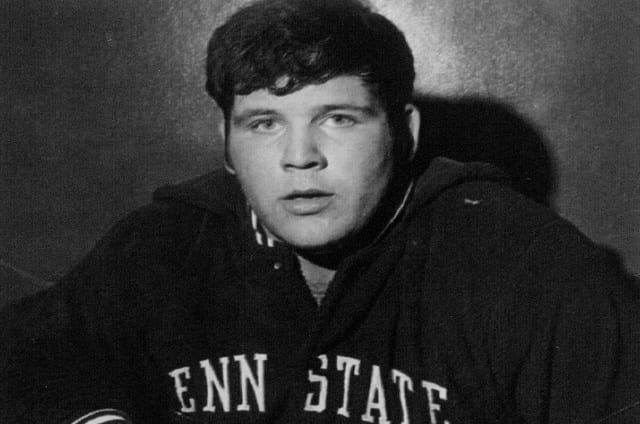

Lubert won three letters at Penn State, posted a career record of 18-3-3 and came within a whisker of making the U.S. Olympic team in 1972. Yet, in his mind, he had failed. In fact, he says, “When I first graduated from school, I used to judge myself through that failure of not being able to compete and win a national championship.”

Ira Lubert compiled a record of 18-3-3 as a Penn State heavyweight in the early 1970s.

* * *

In May of 2002, Ira Lubert spoke to the graduates of Penn State’s Smeal College of Business. Not only did he provide them with that rarest of commodities — a memorable commencement address — but he also shared his secret of success, a healthy response to failure.

“On this, your day of triumph and success,” Lubert told the graduates, “here is my simple message: each of you will fail. Somewhere, sometime — each of you will fail. And those of you who are truly lucky will fail early and often.”

Then he specifically mentioned his epic battles with Dave Joyner. “I was big, strong, fast and fiercely focused,” Lubert told the Smeal grads. “And I lost when it counted most. And I spent probably five years defining myself and thinking about myself in those terms. As the guy who didn’t win when it counted. I had failed.”

But in the business world, Lubert told his audience, the toughness he acquired through failure allowed him to compete with graduates from Harvard, Yale and Princeton. “I may not have had a fancy Ivy League degree,” he said, “but I more than made up for that in my tenacity and ability to focus. I had learned about myself — about my strengths and weaknesses. And I had no delusions about the meaning of victory and defeat. The real stuff in life was elsewhere and had to do with character and integrity… the capability of being the long-distance runner.”

Lubert’s final words that day should be entered into the archives of great commencement conclusions. “Congratulations on your success,” he said. “But don’t forget my simple message. Now go out there and dare to fail!”

IBM, THEN CEO

And that’s what Lubert did after picking up his Penn State sheepskin. He dared to fail, entering the risky business of sales, but he became a big success. Applying his mat-made lessons of courage and determination, he ranked first among IBM’s 4,000 sales people in the U.S. during 1975. And just to prove it wasn’t a fluke, he repeated his number one ranking in 1976.

In the years since, Lubert has achieved even more remarkable success, and he is now CEO of Independence Capital Partners, a holding company with seven private investment firms that manage $20 billion. He sits on numerous corporate boards, and he raises and gives money to support a wide variety of causes, including Penn State and United Way of Greater Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey.

Says Joyner, still one of Lubert’s best friends, “The magnitude of all he’s able to do would make most people gasp for air.” (Joyner, by the way, is an orthopedic surgeon who founded a medical corporation, sat on the Penn State Board of Trustees for more than 10 years and served as PSU’s athletic director for two and a half years.)

SERVING & GIVING

Money attracts attention, so Lubert has gained more notoriety than he would like for his generosity to Penn State. But his involvement is also impressive, especially his continuing membership on the Board of Trustees. So far, he has served three stints on the board for a total of about 12 years, and he is scheduled to remain a member until next year.

Of course, the most difficult period began in November 2011 when charges of sexual abuse were filed against former assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky. Lubert could have simplified his life by leaving the board during that tumultuous time, but anyone who’s wrestled for seven overtimes is not likely to quit. He remained on the board, eventually becoming vice chair and then chair. “In my own way, I felt that I could give back,” he says. “I think Penn State’s in far better hands today than it was. We went through some stormy times, and I honestly believe we’ve come out the other end of it.”

Lubert’s history of Penn State giving shows his diversity of interests. He has offered financial support to the Penn State All-Sports Museum, to the College of Health and Human Development, to Penn State Abington and to the Penn State Great Valley School of Graduate Professional Studies. And his concern for others has prompted him to provide scholarship funds for students from minority backgrounds.

Perhaps closest to his heart, Lubert has consistently assisted the wrestling program. His biggest gift provided a large chunk of the funding for the Lorenzo Wrestling Complex, a fabulous Rec Hall facility that opened in 2006 and may have helped convince Sanderson to come to Penn State in 2009. “I wasn’t going to let them name it after me,” says Rich Lorenzo, a close friend of Lubert who served as Penn State’s head coach from 1979 to 1992. “But then Ira said, ‘Well, then I’m not going to give any money.’’

Ira Lubert (right) and his lifelong friend, Rich Lorenzo, at the 2006 dedication of the Lorenzo Wrestling Complex.

LORENZO A LIFELONG FRIEND

It would be an understatement to say that Lorenzo and Lubert go way back in their friendship. They both hail from Newton, N.J., a small community about 60 miles northwest of New York City. Lubert, a football player at Newton High School, was told by a coach to join the wrestling team in 1966 during his sophomore year. He soon met Lorenzo, one of the team’s most famous graduates who was then wrestling for Penn State. Lorenzo began to help train “the Hairy Bear” during summers and school breaks.

Lubert, eager to add muscle, asked to work on the Lorenzo family farm. That added another dimension to the friendship—and the most undignified story that will ever be told by either of these distinguished gentlemen. “I remember during my high school senior year,” says Lubert, “we were shoveling out the manure in this barn for the calves. Rich inadvertently got some manure on me which started some verbal dialogue, and then him running at me. I flipped him on his back, right into the manure. I had him pinned there, but he took his hand and grabbed a handful of manure and shoved it in my ear. I wasn’t laughing then. He wasn’t laughing either. But after many years — how funny that was.”

He finished his senior year in fine style, winning the state title and posting an overall record of 23-0. Although he leaned strongly toward attending Penn State, other programs sought to change his mind. For example, one coach from the Midwest offered a bold promise: “If you come to our school,” he said, “you’ll be a national champ.” But Lubert told the man, “I want to be a national champ at Penn State.” So the coach persisted and said, “Well, they’ve got Dave Joyner there.” (Joyner enrolled one year before Lubert but then redshirted.) Lubert, still a teenager, turned the tables on a much older man with this simple statement: “Well, I guess if I can’t beat Dave Joyner, I can’t be a national champ.”

Indeed, Lubert chose Penn State because he valued the school’s Eastern location and its combination of academic and athletic excellence. And it just so happened that his mentor and friend, Rich Lorenzo, was graduating and becoming an assistant coach for the Nittany Lions.

Even today, the former Newton wrestlers are like adopted brothers to each other. They sit together every year at the NCAA wrestling championships, playing “Hearts” between sessions (most games are won by Lorenzo’s daughter, Anne). According to Joyner who is another member of this lifelong wrestling fraternity, Lubert and Lorenzo are constantly razzing each other and making crazy wagers like, “I’ll bet you a dollar that I can go without diet soda for a whole year and you can’t.”

RECRUITING CAEL

In the spring of 2009, Penn State’s then-athletic director, Tim Curley, pondered his need for a new head wrestling coach. His first step was to invite four individuals to join him on a search committee: Jan Bortner, an associate athletic director who supervised wrestling; Dr. Scott Kretchmar, Penn State’s faculty representative to the NCAA; Joyner and Lubert. So there they were, the two old rivals and lifelong friends, teamed up on a committee to find a topnotch wrestling coach. And that soon led to a committee meeting with Cael Sanderson, one of a handful of premier coaches they interviewed.

Says Joyner, “I believe Cael was looking for a situation where he could be successful year in and year out. And that entailed finding a community that was committed to having a great wrestling program and also doing it in the right way. And Ira greatly represented that. I think that Ira was a really reassuring presence in transmitting that to Cael.”

According to Lubert, “There was not total unanimity through the first round of interviews. I was very vocal in support of Cael. And I’m very proud of the fact that I was very aggressive in that area, even though it wouldn’t have happened without the entire team, and Tim Curley did a phenomenal job.

“I remember when we interviewed Cael, I asked him what would interest him in leaving Iowa State where he was very successful — the only school that year to qualify all 10 wrestlers for nationals — for Penn State. And his answer showed me that his focus, his plans and his goals were well thought out. I knew right then, after looking in his eyes, that he was the guy and that he was sold on Penn State.”

Today, Lubert admits he was surprised by the speed of Sanderson’s success, bringing a national title to Penn State in just his second year as head coach. “It blew my mind,” says Lubert. But he’s not surprised that Sanderson helped put Penn State among the nation’s top teams.

“The headliner,” notes Lubert, “is ‘Come wrestle for Cael Sanderson.’ But the truth of the matter is you’re wrestling for an unbelievable person in Cael Sanderson who has tremendous values, doesn’t take shortcuts, always has the kid’s best interest at heart.

“That’s why you want a Cael Sanderson at Penn State. And he’s built this dynasty — and it’s not going to end any time soon.”

Ira Lubert enjoys his matside seat at Rec Hall wrestling matches. (Photo by Jennie Yorks)