Spencer Bivens has played baseball for the Rogers State Hillcats, the Lions de Savigny de-sur-Orge, the Steel City Slammin’ Sammies, the Washington Wild Things, the Lexington Legends, the West Virginia Power, the Gastonia Honey Hunters, the Sacramento River Cats, the Eugene Emeralds, the Richmond Flying Squirrels and the Scottsdale Scorpions.

Perhaps you haven’t heard of any of those teams.

This past Sunday, Bivens played for a team you probably have heard of: the San Francisco Giants.

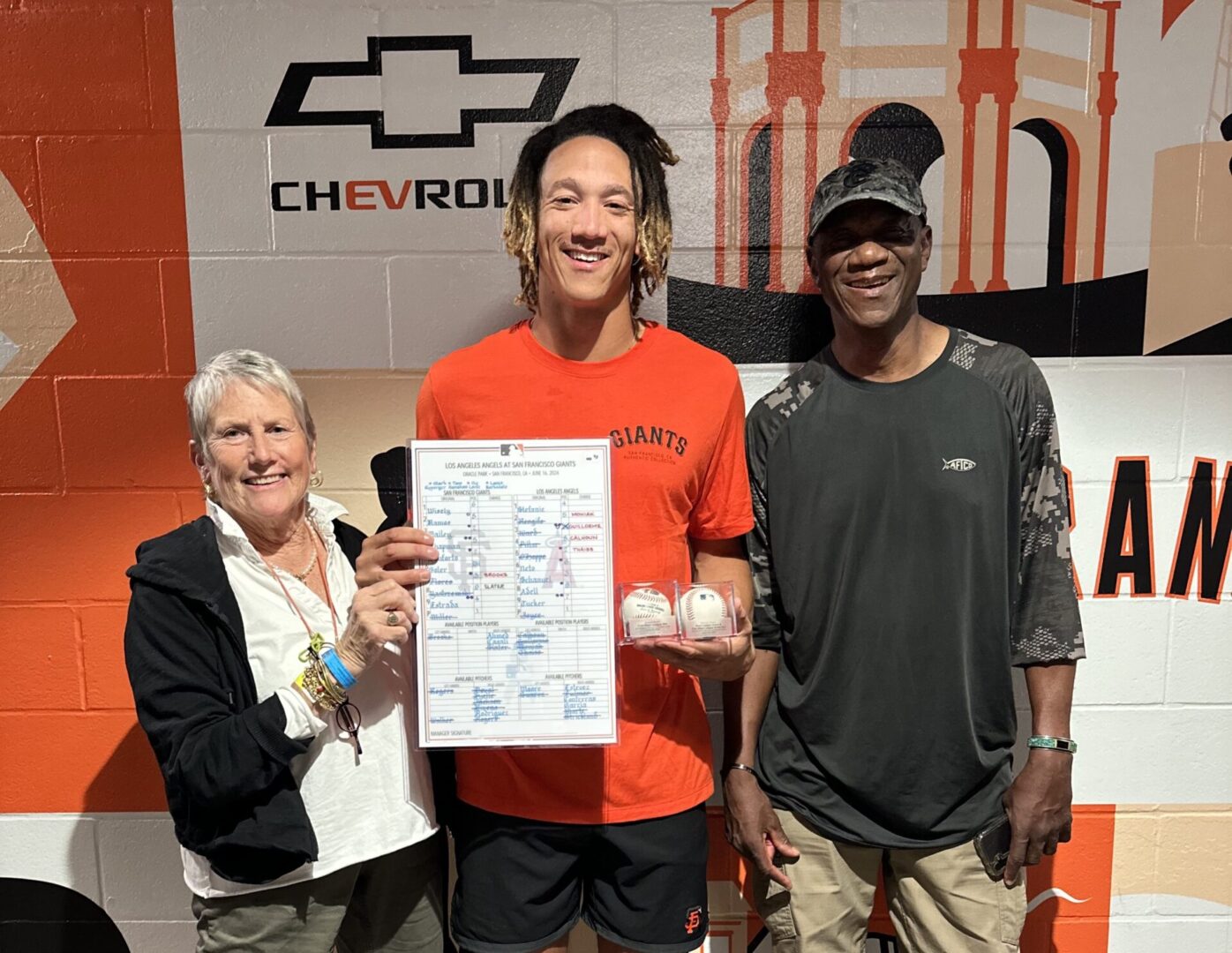

It was his Major League debut, and it was stellar: 3 innings pitched, 4 strikeouts, 1 hit and 1 run allowed. Oh, and he was the winning pitcher in front of a sell-out Father’s Day crowd in San Francisco. Among the faces in the crowd: Bivens’ mom, Caran Aikens.

It’s always a feel-good story when an unheralded athlete toils in obscurity for years and gets the call to the big leagues at an age – Bivens is about to turn 30 — when most guys would have called it quits.

Spencer’s story feels particularly good here in the State College area because here in the State College area is where Spencer was raised. I watched him play when he was a tall, skinny Little Leaguer. He and my son Ethan were teammates and friends, first in Little League and later at State College Area High School.

Remarkably, Spencer wasn’t the best player on any of those teams. When I caught up with him on Tuesday afternoon – he was sitting in the bleachers in Wrigley Field, soaking in the atmosphere before a night game with the Cubs – he mentioned that he was cut from the State High team in 10th grade, struggled to get playing time when he made the team, and wasn’t recruited by any colleges.

By the time he graduated, though, he was good enough to hope he could land a spot on Penn State’s team, but failed a drug test and wound up pitching for Division II Rogers State in Claremore, Oklahoma.

Then, the odyssey began, first in Europe, where he played for a team in the suburbs of Paris, of all places, and then from the Atlantic to the Pacific hopscotching among all those independent and minor league teams.

He got better and faster as he got bigger, but as recently as 2021 he was giving up more than 7 runs per game (anything much over 4 runs per game is considered unworthy of a big-league pitcher). Then, when many players would have let go of the dream, Spencer began putting it all together. The Giants noticed, and signed him.

Last month, as a member of the Triple-A Sacramento River Cats, a string of dominant appearances earned him Pacific Coast League pitcher of the month honors. So when the Giants needed reinforcements last Friday, Spencer got the call.

Then came the whirlwind: a late-night drive to San Francisco from Reno, where the River Cats were playing last weekend; walking into the clubhouse and seeing his name on a locker; big hugs from his new teammates; the call to the bullpen in the second inning; taking the mound before 41,000 fans; and then, afterwards, facing a scrum of sports reporters.

For Caran Aikens, too, it was a whirlwind: Spencer told his mom the news in the wee hours of the morning (there was a lot of laughing and crying, she said), the Giants got her on an early flight to the West Coast and she made it to the ballpark in time for the 1:05 start. Mother and son got to see each other before gametime: more crying.

The first Major League hitter Spencer faced in a game that counted struck out. The second hit a home run.

“He was unrattled,” Caran said. “He suffered so many ups and downs for so long, it didn’t faze him.”

The rest of the hitters went down in order – all eight of them.

On Monday, after another early-morning flight, Caran was back home in Charlottesville, Virginia, texting and phoning as the congratulations poured in. She called it “the craziest 36 hours I’ve ever had – and the most exhilarating.”

Wil Bivens was less lucky: Dad also flew out to San Francisco, but one of his flights was delayed, so he got in too late to see the game.

I asked Caran, who attended the same Little League games I did all those years ago, if she ever told her son it might be time to find another career. She did indeed tell him he ought to have a “Plan B.”

But, she said, “he would convince me: ‘I can make this happen. I know I can.’ To see Spencer so full of joy and achieving what he set his sights on, a parent couldn’t be happier.”

I then asked Spencer, still in the Wrigley bleachers, why he thought his story was getting so much attention.

“It’s about not giving up,” he said. “It can apply to a lot of things in life. There are people who can resonate with that.”