Located in the Whitmore Lab on the Penn State campus, the PAC Herbarium may be one of University Park’s best-kept secrets.

Cabinets and shelves are lined with more than 107,000 carefully dried, preserved, and mounted plant specimens from around the world. The room’s temperature is kept at 69 degrees throughout the year to keep mold and insects away. Treasured specimens collected by Evan Pugh, Penn State’s first president, showcase the legacy of the herbarium and the role it has played in the university’s history as a leader in agricultural sciences.

The herbarium was established with Pugh’s donation of 3,000 specimens in 1859. As a trained chemist with an interest in plants, Pugh began his collection while studying for his Ph.D. in Germany. After accepting his position with Penn State, then known as the Farmers’ High School of Pennsylvania, Pugh brought with him his plant specimen collection and a strong desire for the agricultural school to house an herbarium.

Since then, the PAC (Pennsylvania Agricultural College) specimen count has continued to grow. It now includes vouchered plant specimens from Penn State researchers, a seed collection, and Herbert Wahl’s collection of the North American species of Chenopodium, a weedy annual plant also known as lamb quarters or goosefoot.

As a resource that is available to Penn State faculty, staff, students, and interested members of the public, the PAC provides visitors with opportunities to learn more about how plant diversity and growth location impact the world around them.

Sarah Chamberlain, PAC curator, says these plant and seed specimens house a significant amount of knowledge that can be used in a number of education and research settings. These include plant identification, climate change analysis, gas exchange in plant tissues analysis, soil analysis, plant DNA analysis, entomology, and even new plant discoveries.

“One of the big uses of herbaria collections these days is looking at climate change,” Chamberlain says. “Not only can you look at things like when did the plants flower, but you can go back to the older specimens and compare them to the modern-day specimens. Researchers are finding out that plants are now flowering earlier, sometimes up to two weeks earlier. This is causing a disparity between the plants and the pollinators, which aren’t coming out as early.”

In her role as curator of the herbarium, Chamberlain is responsible for managing the collection – collecting, mounting, preserving, and maintaining the specimens for use by herbarium visitors.

Since joining the PAC in 2015, she has made it her mission to share the wealth of knowledge that she manages with as many people as possible. To do so, Chamberlain has placed a focus on public outreach and education – offering plant identification opportunities, specimen vouchering, tours, and experiential learning workshops to Penn State faculty and students, and local residents and visitors.

Chamberlain says she has worked with members of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy who are interested in the rare, threatened, and endangered plant specimens housed at the PAC. With a goal of finding relic populations of the plants, the conservancy members use the herbarium specimen information to locate and travel to previous plant sites to try to rediscover plant populations.

At a recent STEM day at the PAC, Chamberlain used specimens and plant identification to teach local Girl Scouts about pollinator plants. After asking the scouts to create a key to showcase the characteristics of 10 common pollinator plants, Chamberlain presented the girls with seeds from each of the 10 plants to grow their own gardens at home. The key they created at the herbarium will help them identify the plants as they grow up from the soil. Because of the success of this workshop, Chamberlain hopes to grow the herbarium’s involvement with K-12 students.

Chamberlain also organizes monthly workshops that focus on plant identification or a Penn State faculty member’s plant-based research.

“I’m trying to come up with many different ways to do hands-on learning here,” she says.

Donald Davis, professor in the Department of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology, has experienced this hands-on learning firsthand through workshops and interaction with Chamberlain to identify plants. Because of an interest in understory forest health, he attended a workshop Chamberlain held at the herbarium on ferns. He has also worked with Chamberlain to identify different plant life such as gooseberries, nettles, and various parasitic plants.

As a faculty member interested in biocontrol of invasive plants, diseases in plant life, and the susceptibility of forest plants to ozone, Davis says the herbarium can be compared to a library.

“I use the herbarium to help identify various different plant species and plant diseases,” Davis says. “It’s a great resource of plant specimens that I use for teaching and research purposes.”

Recently, Davis worked with Chamberlain to learn more about identifying buffalo nut, a parasitic shrub found in the Appalachian forests, to use in his undergraduate course on diseases of forest and shade trees. Because of the PAC’s vast collection, Chamberlain was able to provide Davis with buffalo nut specimens for his review.

Having a resource like the herbarium at his disposal is something Davis greatly appreciates. Because of the importance plant diversity plays in the health of forests, having access to the PAC’s collections of plants specimens provides him with opportunities to expand his knowledge of plant diseases and issues that may arise in forests.

“You need a baseline to know if a change in the forest is occurring,” he says. “The herbarium helps identify various different [plant] species to know if a change is happening.”

As the third largest collection of plant specimens in Pennsylvania and the most scientifically functioning herbarium in the region, the PAC is home to five special collections directly related to Pennsylvania and Penn State. The County Floras is a collection of regional plants students gathered from Pennsylvania’s Blair, Centre, Clearfield, Columbia, Huntingdon, Jefferson, Lycoming, and York counties.

The herbarium also houses Herbert Wahl’s Chenopodium collection. Wahl was a former curator of the herbarium and is seen as an expert in this genus of flowering plant.

The Ranunculaceae collection was created from specimen from Wahl; his protégé, Walter Westerfield, and Carl Keener, another former curator of the PAC. The Carex collection includes specimen from Wahl and Keener and includes Paul Rothrock’s Pennsylvania Carex key.

In 2009, the PAC received famous Philadelphian botanist John Harshberger’s tree and shrub collection from Penn State Mont Alto’s herbarium. The herbarium also houses type specimens, specimens that are chosen as the reference sample of a plant when the species is first named. Currently, the PAC has 62 North American type specimens.

Continuing to grow the PAC’s collection is something on which Chamberlain places a large focus – especially as herbaria are becoming few and far between.

“An herbarium is integral to anything that is done in plant science,” she says.

Because of the importance of botany and collections like those housed at the PAC, Chamberlain says Penn State has endorsed the formation of a museum consortium at the University Park campus. This consortium will include art collections, sports collections, and natural history collections like those at the herbarium.

“Botany is starting to come back and Penn State recognizes that there is a real threat if these collections go away,” she says.

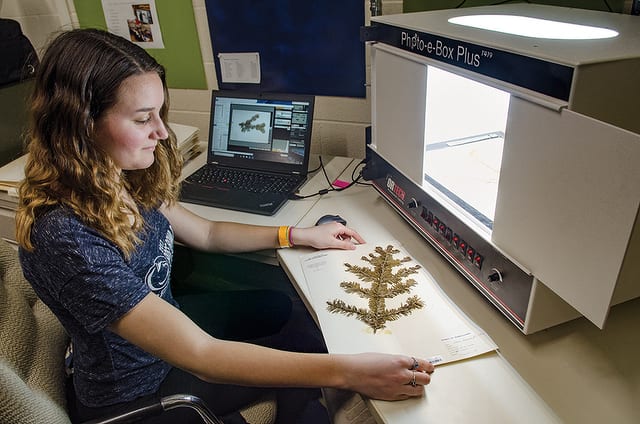

To preserve the PAC’s collections digitally, Chamberlain, with the help of two student interns, is using a grant from the National Science Foundation’s iDigBio program to image herbarium specimen. For the next three years, work will be completed to image and database all specimens in the PAC’s collection from Pennsylvania and the Mid-Atlantic region. As a part of the grant, the PAC applied to become a Partner to an Existing Network, or PEN, to the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project, a Thematic Collection Network, or TCN. The iDigBio program defines a TCN as a network of institutions with a strategy for digitizing information that addresses a particular theme, such as plant specimens.

“Our goal is having the entire collection imaged and online, allowing our specimens to be digitally searched for and used,” Chamberlain says.

“It’s amazing the information that is in these specimens that no one would suspect. I read a paper not that long ago that said 50 percent of all the new plant discoveries are being found in herbaria. People will go back and look at old specimens and find that something was mislabeled and it’s actually a new species. If we didn’t have these herbaria and their specimens, we wouldn’t have this information. There’s not really another place [people] can come in order to get information. The need and the desire [to have herbaria] is great.”

For more on the PAC, visit sites.psu.edu/herbarium. Samantha Chavanic is a freelance writer living in Bellefonte.