My mailing address says, “State College,” my tax bill says, “Patton Township,” but when someone local asks, I say I live in “Park Forest,” and most people in the “Centre Region” will know where to situate me. But these geographic facts don’t tell us much about the evolution of places in which we live and work.

One of the Centre County books that I’ve always found particularly useful for this purpose is a volume published in 1961. Local history buffs will quickly recall Where to Go and Place-Names of Centre County, by Paul M. Dubbs. A Bellefonte native, Dubbs began his newspaper career with The Republican in Bellefonte shortly before it ceased publication in 1925. He then spent 20 years with the Centre Democrat, before becoming the county editor for the Centre Daily Times in 1953, staying with the CDT for 45 years.

This encyclopedia of Centre County local lore was compiled from CDT columns Dubbs wrote in 1959 and 1960. “Where to Go” columns came from reader queries about where to spend a day in Centre County, while the “Place-Names” articles responded to numerous “never heard of it” and “just exactly where is that place” comments.

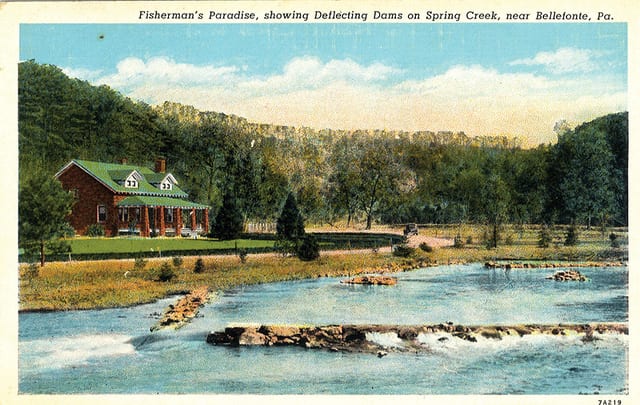

The book’s first 16 pages describe, in alphabetical order, every site and view of note from the Bass Hatchery at Fishermen’s Paradise to Woodward Cave in eastern Haines Township. Dubbs details a variety of scenic drives, views and parks, as well as a couple of ghost towns like Scotia and Poe Mills (a lumber town where Poe Paddy State Park is today).

The place names section identifies about 270 boroughs, townships, villages, hamlets, railroad stops, and identifiable places, past and present, in the county as of 1960, many that can no longer be found on a modern map. But there’s history aplenty for those with deeper interests.

In Patton Township, for example, Dubbs compares two developments across Route 322 from each other. One was Woodycrest, “a town which grew without much planning” and the other Park Forest Village, which was “one of the county’s most completely planned villages.”

Woodycrest was developed from a 65-acre farm by W.A. Strouse, who moved there in 1927. He began selling lots for $20 to $50 each (although he sold the first one for 30 chickens). He helped many of the first residents finance the building materials for the small homes which were built “as they pleased.” He also donated rights of way for streets, 4 acres for a park, and a lot for an Evangelical United Brethren Church (today the Woodycrest United Methodist Church, on West Clearview Avenue).

Across the highway lay the beginnings of Park Forest Village, which welcomed its first family, Mr. and Mrs. Lyle E. Shoot at 1882 Park Forest Avenue, in 1956. The village had been in the planning and early development stages for nearly a decade before that. The developer was J. Alvin Hawbaker, with land planning by Carl Wild of State College, and architecture and site planning by Charles M. Goodman of Washington, D.C.

By 1960, there were almost 200 homes occupied or under construction and the village had won two national awards for its innovative site planning. Plans then called for more than 1,000 homes, a shopping center, elementary school, apartments, a motel and restaurant, a swimming pool, and other amenities. By 1960, there was also bus service between downtown and Park Forest with 17 scheduled round-trips per day.

Almost 60 years later, Woodycrest has become a small enclave of affordable housing and Park Forest sprawls over parts of Patton and Ferguson townships with a population of almost 10,000 alone (it is a “census-designated place,” so its numbers are counted).

The 1932 creation of U.S. Route 322 constructed between downtown and Martha Furnace in the Bald Eagle Valley replaced a meandering dirt road that went from College Heights to the Bellefonte Central Railroad stop at Waddle, near today’s I-99 Waddle interchange and Toftrees, another enormous planned residential development with thousands of citizens.

Overall, Dubb’s Place-Names provides a mass of fascinating details. From Aqua, Bananatown, and Frogtown to Gum Stump, Sober, and Tangletown, who can resist wanting to know more about these places and what happened to them?

At the same time, Dubbs helps us trace “suburbanization” in Centre County as farms on the edges of towns are gradually changed into named housing developments and sometimes annexed by boroughs.

Lytle’s Addition for example, evolved on the southern edge of State College as, in Dubbs’ words, “a kind of slum settlement.” It was annexed by the borough from College Township in 1932, and gradually improved with paved streets and modern buildings.

But, hidden among the details, we learn that as the cost of living in Lytle’s Addition crept up, some residents moved to the less expensive Woodycrest area. Clearly, affordable housing is not just a recent issue. Place names are more than just curiosities, their stories have lessons to teach as well.

Lee Stout is librarian emeritus, special collections, for Penn State.