This story first appeared in PA Local, a weekly newsletter by Spotlight PA taking a fresh, positive look at the incredible people, beautiful places and delicious food of Pennsylvania. Sign up for free here.

I think my new house might be haunted.

I’ve not experienced anything particularly unnerving there, to be clear. No apparitions. No voices. No sudden chills or shut doors. (There was a night light in the bathroom that violently strobed every time I walked by, but I’m pretty sure that was just a faulty sensor. Pretty sure.)

My suspicions have to do with the age of the place — it’s almost as old as the Civil War — and its location: It directly abuts a former lumber mill that a neighbor, while struggling against the pull of his formidable corgi, told me was likely the scene of grisly accidents long ago.

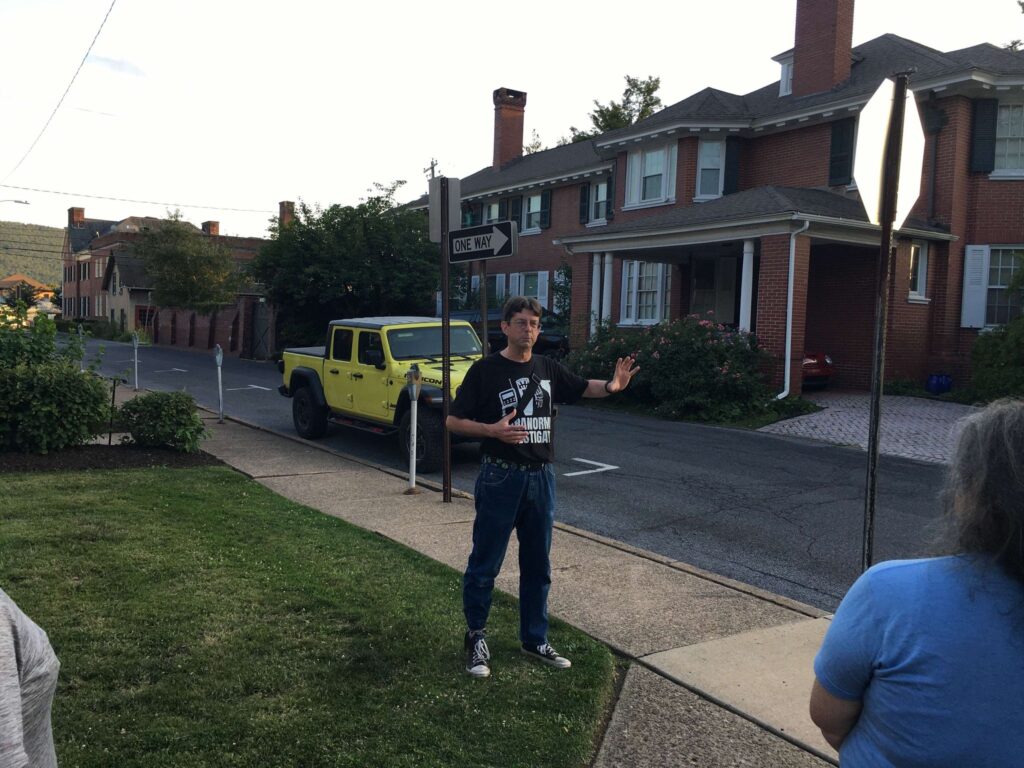

So what do you do if you suspect your place might be possessed and you want to learn more? I asked Lou Bernard, a Clinton County-based paranormal investigator, author and historian.

We covered DIY research tips, the ethics of ghost hunting and why some people feel comforted when they finally meet their phantom. The conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

PA Local: Lou, I think my house might have some history. I’ve asked you to share some paranormal research tips, but first, can you tell me about the work you do for others?

Bernard: Yes. I’m part of a ghost hunting team, the Lock Haven Paranormal Seekers, and that’s part of our service. I actually will do a title search on the house, and, you know, find out who is most likely to be haunting the place for you.

Once we’ve done all that, that’s the point where the occupant decides whether or not they’d like an investigation. We get people who assume we’re going to come in with candles or proton packs and rid the house of their ghost. We’re investigators, not exterminators.

We have cameras. We have digital recorders. We use laser thermometers and devices that detect electromagnetic fields. And we will just go in, set up stuff, pay close attention to the instruments and look for evidence or anomalies.

We typically do four to eight of these in a given year.

What does all this cost?

We do it for free. Now, if you feel like making us a dip or something, great, but that’s not required. In my opinion it’s not really ethical to charge money for this.

Why’s that?

Say the sound the occupant is hearing is a loose pipe. You want to be able to tell them that. It’s very important to be able to say, “We found nothing.” I met a guy once who charged $1,500 per investigation. He has 1,500 reasons to find something, whether he found something or not.

Does anyone ever regret learning more?

Yeah, I suppose you could say that. Sometimes we will do an investigation and we’ll find out that there was someone who died in the house, and it depends on the type of person, but that makes some people nervous. I will say there is really no danger to this. TV and the movies really fluff it up. Most of the time people tend to feel better after we’re done.

How so?

It’s one thing to be scared of this faceless, nameless sound in the night. It’s quite another to be scared of, like, the five year old who died of cancer 50 years ago.

Here in Clinton County, there was a family that was just scared to death because they were having stuff happen in their home. A lot of it centered around the dad. They thought he was being attacked. And it turned out it was just a little boy — Vincent, I believe was the name. He’d passed away, I want to say from measles complications. And once they found that out, it seemed a lot less scary and intimidating. It was just a little boy who missed his own dad.

This may be an obvious question, but do you believe in ghosts?

Well, it’s an obvious question with a not-so-obvious answer.

My response tends to be that if I believed I wouldn’t have to investigate. You’re a bad scientist if you’ve already decided what the outcome of the experiment is, right? I will say I’ve seen some evidence that persuades me that there’s stuff we don’t understand.

OK, so if I wanted to do some research myself, where should I start?

If you own the house, the process has been started for you.

In Pennsylvania, you’re required to have a title search done going back 50 years before you can buy a house. But assuming you’ve owned the house for 20 years and can’t lay hands on the title search, which does happen, what you would do is go to the courthouse.

I always start with the assessment office. That’s where they keep the records when it’s been assessed for taxes. All you gotta do is ask, based on your address, and they will find a copy for you. It’ll list on it the most recent couple of deeds. They’re labeled by books and pages generally, so it’ll say something like, “Book 157, Page 203,” or whatever.

Using that you go down to the register and recorder’s office. You pull that particular book, go to that page and it should have the most recent deed, presumably, where you or the current owner bought the house. You can use that deed to find the previous deed and so on, and you should be able to trace it all the way back to the beginning of your county. (Editor’s note: Pennsylvania’s state library also suggests the state archives’ searchable index of land records for older properties, and an online land records and deeds directory for younger properties.)

How do you know when you’ve reached the beginning of a house’s life?

Deeds have improvement clauses that say something like, “improvements include a two-story frame house with detached garage.” That means improvements to the land, as a general rule, and if you start to find deeds without an improvement clause, the house hadn’t been built yet; you’re at the beginning.

What if the property is a rental?

In that case, knowing who owned the property isn’t necessarily going to tell you much, so there you look for something called a city directory. It’s like a reverse phone book, and each city directory, year to year, should have a list at any given property of who lived there.

Where can I find a city directory?

Libraries, historical societies, museums. Those are the places I check.

Now that I’ve got the deeds and a start date, what do I do?

The deeds will say who bought it and who sold it, and you want to copy that information down, because a lot of the time that’s who lived there.

Once you’ve got a list of all the people who lived there from when the house was built, then you go to the local newspaper, library, historical society — that part will vary a bit — and find out where the obits and the newspaper archives are kept.

Check obituaries, cemetery records, findagrave.com. Usually, deeds will list the one main guy who owned the house, the dad of the family. The obit will tell you when and how he died. And it’ll also tell you who the rest of the family was.

Let’s say a three-year-old child dies in the house. They’re not likely to have an obit, but they’ll have a gravestone. So you know, that’s how you can find out that that kid passed away.

What you’re looking for is generally not death from old age but rather young death and violent death. That’s the kind of thing that causes a haunting.

Check out our previous coverage of Pennsylvania’s odd, paranormal history:

- Inside the queer, witchy ‘they bar’ of Millvale, Pa.

- Is an end to Pa.’s 163-year ban on fortune telling in the cards? One tarot reader is suing to make it happen.

- Meet the podcaster, author and hairstylist bringing Pa.’s haunted history to life

- How a psychic started Pennsylvania’s strangest treasure hunt

BEFORE YOU GO… If you learned something from this article, pay it forward and contribute to Spotlight PA at spotlightpa.org/donate. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.