Bellefonte is celebrated for its role in the Underground Railroad, and for the Quaker ironmasters who assisted and employed Blacks fleeing slavery. Far less is known about the daily lives and contributions of Blacks in Centre County during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including those who played crucial roles in Underground Railroad operations.

The Black History in Centre County Project is a new volunteer-based collaboration dedicated to finding and sharing information about this often-overlooked group. The project is building on the prior research of local historians and genealogists, and is actively seeking Black family history information from the public and local institutions.

The idea for the project began after librarian Racine Amos joined the Penn State University Libraries in summer 2019 and became curious about the contributions that Blacks had made in this area. The January 2021 death of the Reverend Dr. Donna King, pastor of St. Paul AME Church in Bellefonte, who was a highly regarded historian of local Black history, helped Amos decide the direction of her research.

“I’m hoping to open people’s eyes to the contributions that were made, especially in central PA and Centre County, by people of color,” she says.

Ben Goldman, the university archivist, connected her with Julia Spicher Kasdorf, a professor of English and documentary poet who shared Amos’s desire to preserve local Black history.

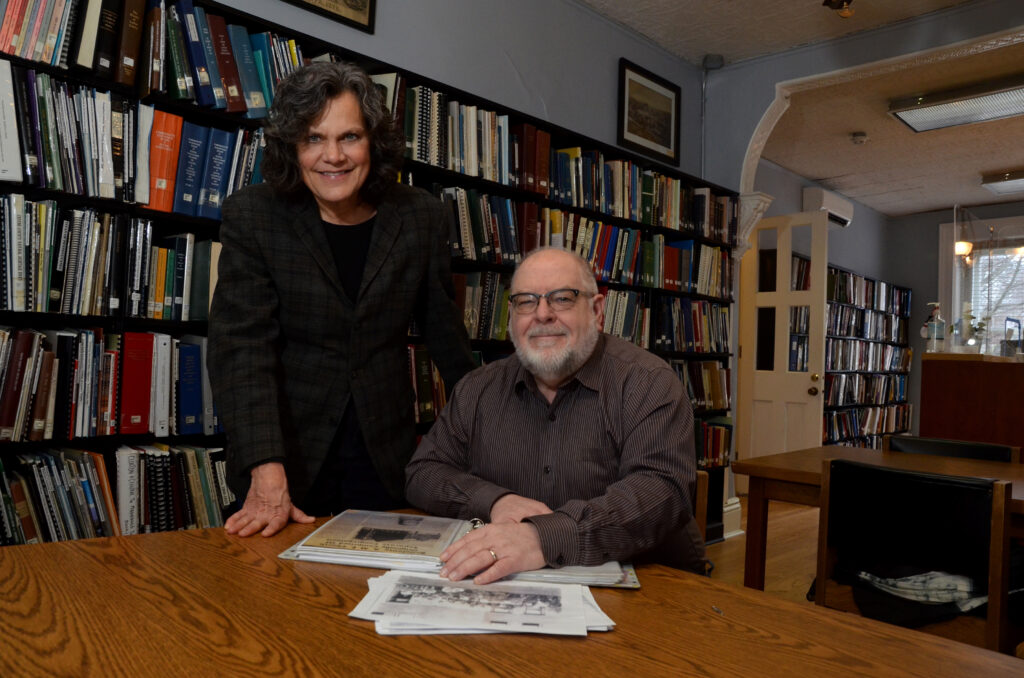

Amos, who now serves as the community engagement archivist and librarian for Penn State, and Kasdorf joined forces and launched the project as co-directors, with Kasdorf’s husband, historian Philip Ruth, as coordinator of the research team.

Kasdorf applied for a competitive digital humanities grant but the project wasn’t selected for funding.

“At that point, we were in it so deep already that Phil and I and the rest of the team said we’re going to do it anyway,” Kasdorf says. “We’re going to find a way to make it work because it’s so fascinating, it’s so fun, and it’s so necessary.”

The current Black History in Centre County Project team includes Amos, Kasdorf, Ruth, Nathan Piekielek, graduate intern Carmen Wong, and Bethann Rea, the digital collections management librarian in the University Libraries. Piekielek, a geospatial services librarian and associate professor of geography at Penn State, will help create local Black history tours. Wong is writing a script for a presentation in April. During 2022, undergraduate intern Jada Yolich assisted with census record research, and undergraduate intern Jenna Lugo drafted a blog post.

The project has benefited from the research and work of others, including King, Jaqueline Melander, Sue Hannegan, Patricia House, Robbin Degeratu, Elizabeth Lose, Sue Kellerman, Mack Mahan, Charles Blockson, and Daniel Clemson. Local genealogist Constance Cole is a consultant on the project and the author of The Black, Mulatto, and Allied Families of Centre County.

Missing links in the paper trail

Leading the research team, Ruth has more than 30 years of experience in public history, including his current role as director of research for Cultural Heritage Research Services Inc. in Lansdale. He says, “One of the many challenges of this kind of research is that the kinds of solid evidence that I usually [use] to reconstruct somebody’s life or the evolution of a community—including things like birth certificates, marriage certificates, even ages reported on census schedules—it’s really dicey and iffy. The dates on the census records don’t always match the dates on death certificates.”

He found few real estate transaction records, marriage licenses, or photographs of early Centre County Black residents, and discovered a large number of foster parents, foster grandparents, and adoptions, which further muddied the waters. “White folks tend to be recorded more dependably in the mid-nineteenth century,” he says.

Amos says another cause for the lack of records is the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The act gave owners of enslaved people and their agents the right to search for escaped slaves within the borders of free states, compelled people to assist in the capture of runaways, and denied runaways the right to a jury trial. The penalty for interfering with the process of recapturing slaves was up to $1,000 and six months in jail.

“Although all Fugitive Slave Acts were repealed on June 28, 1864, it makes it hard to do this research because of the fact that people couldn’t keep records because it would implicate them,” Amos says.

Ruth adds, “In 1860 after the passage of this act, in the midst of this period where there were slave catchers coming north, a lot of the people who had reported being born in Virginia or Maryland in 1850 suddenly claimed that they were born in PA.”

“We do have accounts of slave catchers coming into Bellefonte and nabbing people,” Kasdorf says. “It was a real terror.”

Ruth discussed questions and insights generated by his research. He found that the first cluster of Black families in Bellefonte lived around the old Wesleyan AME Church on East Logan Street. When the Bethelite AME Church was built across the creek on Half Moon Hill, the Black population moved there or created a second cluster, and the area was called Cheapside.

He says, “One of the larger research questions that I’ve been operating under is, how do we account for the loss of this significant Black presence in Centre County that was remarkable and notable in the nineteenth century and then was almost nonexistent by World War II? We’ve been starting with mid-nineteenth century census data and are working our way forward in time so have not processed in any detail twentieth century records yet. It was a precipitous decline.”

After the Civil War, the Black population in Philipsburg grew and became a Black community (smaller than the one in Bellefonte) with an AME Church, Ruth says. Some residents moved there from Bellefonte and Milesburg for employment.

Amos says some Black men worked in the Philipsburg Tannery, and many migrated to upstate New York when the tannery closed.

A small Black community formed near Stormstown at an isolated place called Tow Hill on the western edge of the Scotia Barrens prior to 1850, Ruth says. They did subsistence living and may have moved there because of the Quaker community at neighboring Stormstown, associated with the Way family. In the 1850 census, the household of Isaac Way, who was white, included thirteen black children between the ages of one and fifteen.

“There are things like that, that pop up out of the records that just make you wonder what’s going on here?” Ruth says. “Who are these people? How did they come there? What are their relationships? Where did they end up going?” He says the Tow Hill community dissolved around 1880 when an ore mining company forced them out. Most relocated to the northwest edge of the Scotia Barrens and built a new community, Marysville.

“All kinds of things like that just unspool as you dig up more and more information and then put it in both chronological order and familial order,” Ruth says. “I find obituaries of people and newspaper accounts in local newspapers that begin to flesh out these folks’ lives, and you find out new connections. It just gives you a much richer sense of what life was like for these folks.”

He says most Black people who lived in the area at the time did menial labor. “The only job that seemed to offer an ability beyond service with any kind of professional qualifications was barbering. And so there was a plethora of Black barbers in Bellefonte from the 1850s through the 1890s. Some barbers moved to neighboring communities. They were able to accrue resources, to buy real estate, and to do more than just subsist day to day on hourly or day to day wages like most of the Black people in Centre County.”

Many moved to other cities. Ruth says, “It was a diaspora that I think worked against keeping the oral history of Black experience in Centre County local.”

Opportunities for the public

The research discoveries will be available to the public through the website, blog, activities, and events. On April 21 and 23, the group will host two performances in State College and Bellefonte that include historic choral songs, directed by music professor emeritus Tony Leach, and dramatic monologues written by Wong that are based on historic Black residents.

The project’s historic images database will be publicly accessible for free beginning in April, Amos says.

The first group of images will be from the Pennsylvania Room collection of the Centre County Library and Historical Museum in Bellefonte. Amos and Rea are working with Bonnie Goble and Judy Dombrowski, co-branch managers of the Pennsylvania Room, to select and scan documents and photos.

Amos and Ruth consulted with a Leadership Centre County Junto project group to help develop an Underground Railroad walking tour in Bellefonte. (Town&Gown partner Local Historia was also involved.)

Amos hopes that, in addition to academic and family researchers, K-12 schools will make use of the data and images for their lesson plans and student research projects.

She says, “The ultimate goal is for this project to become a model for other academic research libraries and institutions to foster community-focused and -driven engagement to highlight the lost or forgotten historical narratives of all contributing members of communities.”

“We hope to work with Nathan Piekielek and the University Libraries to develop digital resources, such as tours, to raise public awareness of Black history in Centre County,” Kasdorf says.

With the support of University Libraries experts, Amos hopes to schedule days for the public to bring in their Black family records and heirlooms by appointment to be photographed, and to share their family histories. She hopes to offer advice for preserving and organizing collections. All items will be returned to the owners.

The project team will post events on the WPSU community calendar and the Black History in Centre County Project website. A contact form is available on the website, blkctrco.psu.edu, to schedule appointments or to volunteer.

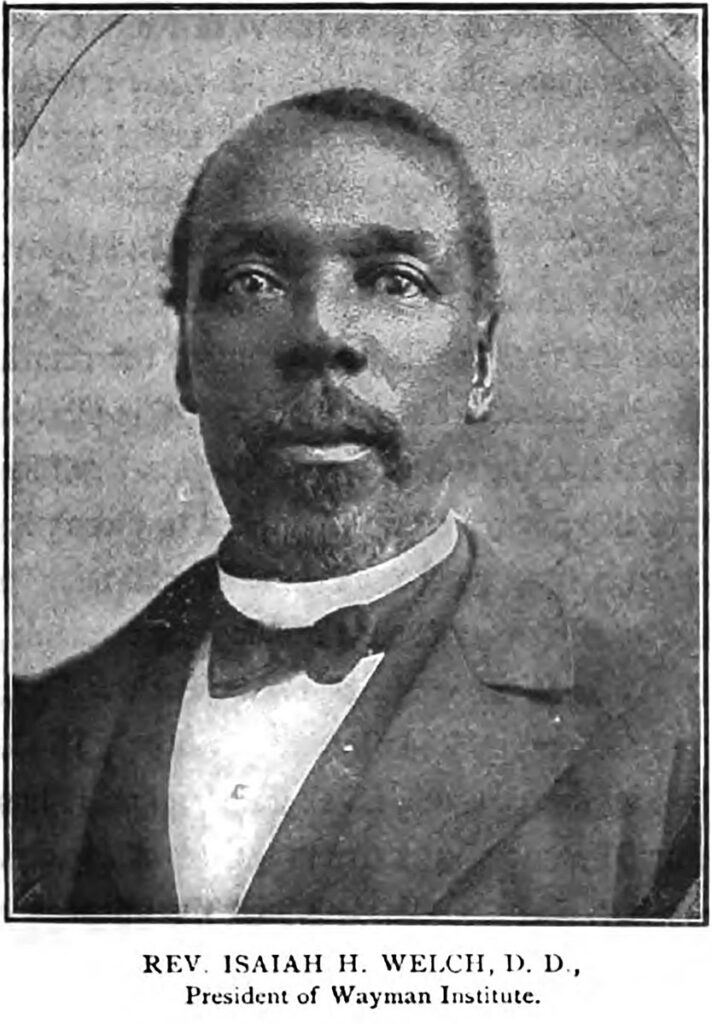

Research Summary: Isaiah Henderson Welch (ca. 1842–1914)

Reverend Dr. Isaiah Henderson Welch was born into slavery as the eldest child of John and Maria Welch. His family escaped from the Eastern Shore of Maryland to Bellefonte. Welch worked as a domestic servant; then he and his father farmed for H.N. McAllister. He attended Wilberforce University in Ohio. In 1863, he left school to enlist in the Colored Troops of the 55th Massachusetts Infantry and was promoted to first sergeant. He was a member of Wilberforce’s first graduating class in 1870 and soon was ordained an elder by Bishop D.A. Payne.

In 1872, Welch married Harriet W. Woodson, with whom he had two sons. He was appointed a clerk of customs in Pensacola, Florida, and served various AME congregations as a pastor and elder. In 1890, he helped establish Wayman Institute, an elementary school, in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, and was president for 10 years. He wrote about the origin and history of the AME Church and donated to help rebuild St. Paul AME Church in Bellefonte after it was destroyed by a fire. He died in Fayetteville, Tennessee, and was buried Frankfort, Kentucky. T&G

Read more stories of local Black history brought to light by the Black History in Centre County Project in the February issue of Town&Gown, available free around the county and online at townandgown.com.

Karen Dabney is a freelance writer in State College.