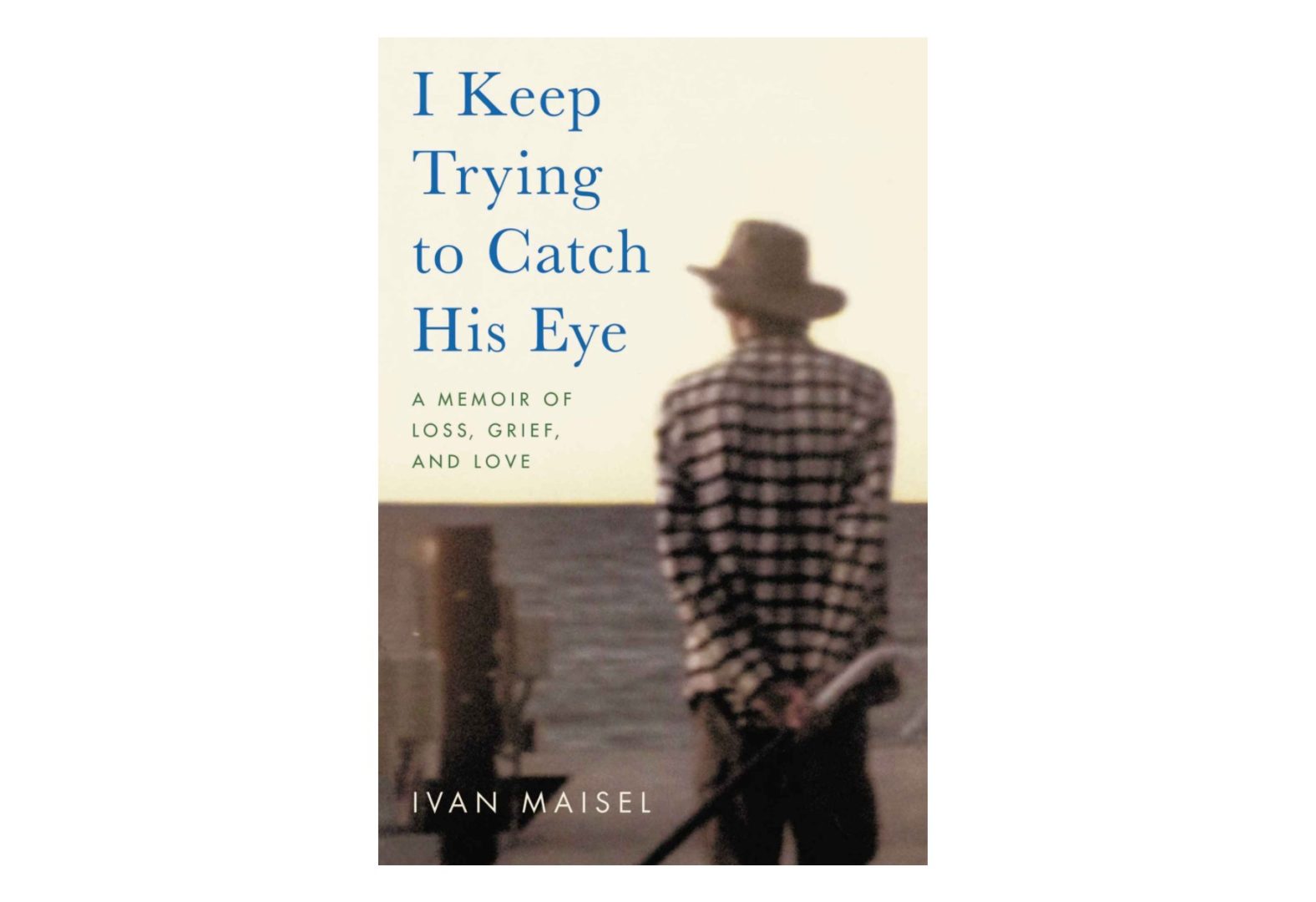

The respected and talented college football writer Ivan Maisel this week released a book that is a gift and a lesson for all of us.

“I Keep Trying to Catch His Eye: A Memoir of Loss, Grief and Love” recounts the loss of Ivan’s son Max to suicide in February of 2015 and the path of grief that followed.

Ivan is one of the really accomplished college football writers in this country. In my years of coaching, he was always fair, professional and someone who became a friend. Everyone in both the media and coaching respects him personally and professionally.

What he has shared and written in the pages of this book is filled with powerful and personal emotions. At a time when the 24/7 smartphone pace of life has created a frenzied disconnect from moments when we can quiet our minds, this book has tremendous value.

When a parent first holds their child in their hands, there is always the expectation that your child will live well past your time on Earth. That is how it is supposed to work. It is the natural order of things.

In August, after reading an advance copy, we had Ivan on the show “Nittany Game Week” to talk about his book. During that interview, Ivan said that he did not want his son to be remembered only for that last act.

The book gives us insight into Max’s life. The talented photographer, the son that was both close and at other times just out of reach. The moments together at New Jersey Nets games became exclusively a father/son thing even though Max did not take the same burning interest in sports that were so much a part of his father’s career.

There was a thread about a tiny white elephant that Max was given as a toddler and the connection he had to it. For years, he was inseparable from it, and there are stories of searching for that lost elephant. He outgrew the attachment but after he died that small piece of his childhood became so meaningful for Ivan’s wife, Meg.

But as important as it was for Ivan to share Max’s story, there is also an honest telling of the difficulties that faced them. They are questions that one suspects we might ask if we were in their shoes. But we are not. We cannot know that pain.

But Ivan Maisel bears that pain.

Writers often try to write through the pain and Ivan was no different. This book shares some of the things he wrote contemporaneously, many of which most of us would keep hidden. He learned that avoidance of grief cannot bring peace.

“Those who choose to stiff-arm the grief will find their arms get awfully tired after a while,” he wrote.

He reveals steps on the climb and goes into detail about the struggle of grief that he and his family have.

Shortly after Max’s death, their daughter Sarah asks Meg and Ivan if they will be getting divorced, because so many couples do get divorced in the aftermath of a child’s death. Often that burden of grief takes its toll and the weight of it becomes a crushing force.

Meg and Ivan came to an understanding, within a week or so of Max’s death, that they would not judge each other’s grief. The road through the challenges of loss would be different, and neither would judge what that road looked like.

Meg wanted to know everything she could about the events that led to the end of Max’s life. Ivan took a different approach. They came to terms as best they could, each in their own way. Most importantly they respected each other’s journey.

But there were moments of anger, of pain that Ivan shares.

“I didn’t grab him and shake him and say what is wrong? We can help! Two weeks ago, I think, and I don’t remember if I wrote this or not, but I drove down the street, repeating louder and louder, ‘We would have done anything!’ until I shouted it, and then my voice cracked, and I said it twice more in an emotional, exhausted rasp. We didn’t know. The we may never know awful. The questions he left. The he was a good son and we took that for granted awful. That one hit me yesterday. Max was a good son. He did what he was asked. He was utterly devoted to us. The we no longer have him awful. The we want our life back awful. The emptiness awful. The pit in the stomach. Feeling like an amputee. The energy it takes to re-enter the civilian world awful. People are living their lives, as we did, and have no idea what it takes to step into that, to think and focus on other subjects, to laugh, to move on. As much concern as they express and continue to express for us, they move on. They get to move on. We remain behind. We carry the burden. They don’t.”

But the book teaches us that ultimately we all must grieve in our own way. And even then, we will feel a tug pulling us back, wishing we could be on the other, brighter side of the wall of loss that bisects our lives into the before and after of that one day.

In one instance he writes: “Everywhere I go, his absence will go with me, stand beside me.” But a few weeks later his thinking turns to a tearful moment in the cemetery when he tells himself, “I have to keep going but I don’t want to leave him behind.” And at another time he writes: “I worry that moving on is callous, too black and white, a shrug of acceptance when I should cling to what I can bring with me of my son.”

It is one of the great paradoxes of our humanity: the desire to hold on to what has passed despite an understanding that the past cannot be undone. Life becomes a series of dates, milestones never reached, birthdays that remind us of the lost potential.

But with Max’s loss, Ivan confides a theme that echoes one from Norman Maclean’s masterpiece “A River Runs Through It.” Ivan says “I didn’t always understand him. But all I wanted for him was to be happy, to find happiness. He wanted to get there and he couldn’t get there.”

Maclean’s book recalls the final sermon he heard from his minister father “We are called to love completely without complete understanding.”

For those who read this work, we see Max as he was. We see a family that makes the best they can through a time of grief. And we see that the human spirit, the will to both hold on and move on are both valid and necessary.

In that final understanding we find a way into each day’s new dawn. And for that and so much more, I cannot recommend this book enough.