The age of iron was ending.

For over a century, the Juniata Iron region of central Pennsylvania had dominated the iron market. The geographic region combined all the essential ingredients for high-quality iron making in one location. Throughout the 1800s, towns would blossom into cities around furnaces and forges, connected by a spider web of railways. The once-daunting Alleghenies had been conquered by man, and industry was king. Families like Benner, Patton, Miles, Curtin, and Valentine made their mark on the history of Centre County through iron, but there was a new industrial power exploding onto the world stage: steel.

More durable and much stronger, steel provided the ability to build greater structures than iron ever could. The prohibitive problem around steel until the 1870s was cost. With the advent of new technologies and a visionary entrepreneur, steel became the most important building material in the world, and Centre County played its part.

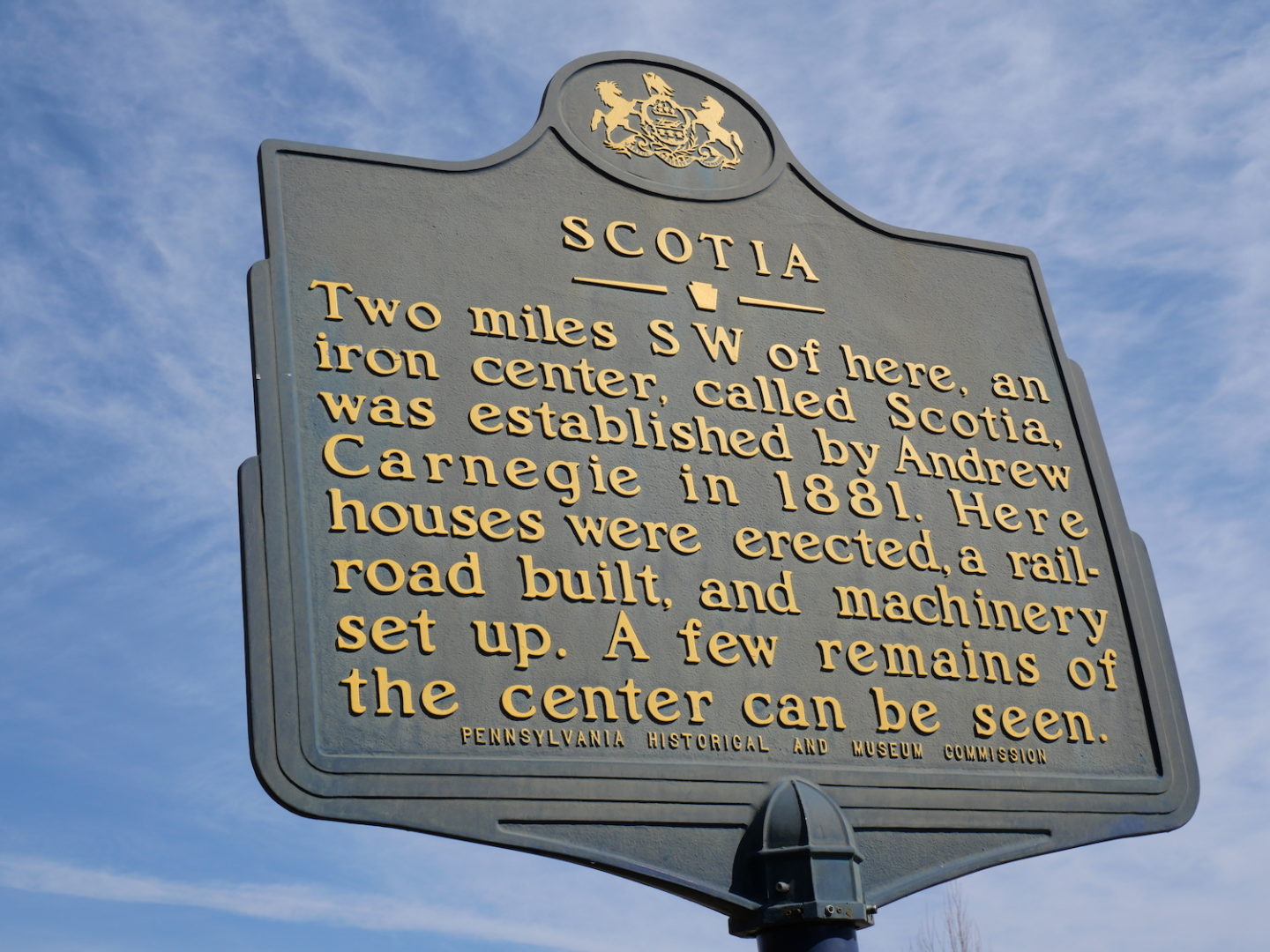

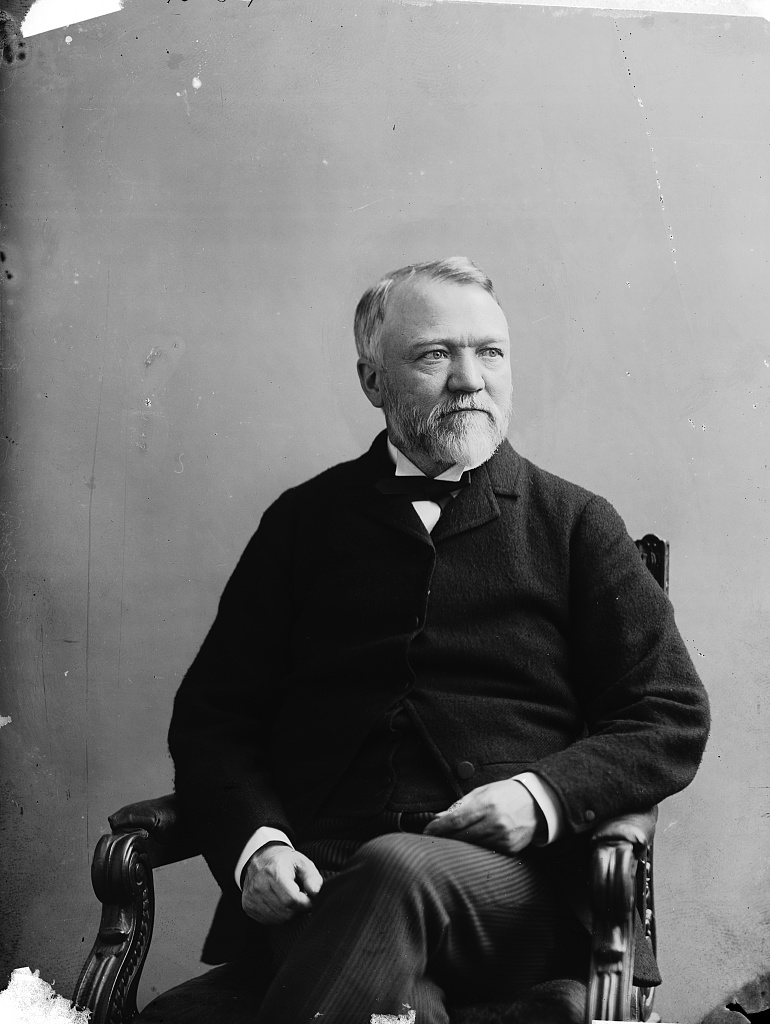

In the late 1870s, the richest man in the world made his way to Bellefonte. Andrew Carnegie was well aware of the area’s high-quality iron products and vast deposits of ore still waiting to be mined in Centre County, and was interested in the possibility of buying some tracts. Shipping iron ore from this area to his mills in Pittsburgh would be far cheaper than shipping from plots further east, and the area was already carved by railways. After surveying the land, Carnegie made his offer. The Edgar Thompson Steel Company, one of Carnegie’s ventures in Braddock, acquired roughly 700 acres of an area that became known as the Scotia range.

Carnegie’s mining operations in Scotia commenced in 1880. Just like the iron towns a century earlier, a village of miners and tradesmen grew in the barrens. Scotia boomed, adding a church, school, and community center complete with a library for the 400 residents of Scotia. The town even had a popular “Scotia Cornet Band,” who in 1897 were given a full set of gold-mounted silver instruments by Carnegie himself! The employees of the steel company even benefited from factory strikes in Pittsburgh and Braddock in 1888, after which the company began providing aid in home building and company savings accounts with 6 percent interest.

The mining was done in an open pit, with ore being washed and loaded onto carts for transport to railcars. In 1881, Carnegie further streamlined the process by having a short line connected to Scotia off the Lewisburg and Tyrone branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad. This allowed iron ore, and the relatively isolated inhabitants of the village, to connect to cities like Bellefonte, and further to Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Carnegie was fully ingrained in the communities of Centre County, establishing working relationships with the likes of James Beaver and Daniel Hastings. As typical with Carnegie, he even gifted the Bellefonte Academy an entire library of books in 1898. Scotia had all the makings to become an industrial city: transportation, resources, land, and the greatest financial backer of the era. That would all come to a halt in 1899.

The same economic genius that brought Carnegie to Centre County in 1879 would lead him away two decades later, ushering in a new era in Scotia’s short history. After squeezing Scotia of roughly $10 million in iron ore, Carnegie saw the area quickly becoming depleted. He sold his entire stake in Scotia to willing buyers in the Bellefonte Furnace Company, Collins Iron Company, Red Bank, and Mattern Bank. After purchase, the Bellefonte Central Railroad would add a spur into Scotia, eliminating the need to backtrack to Tyrone before making its way to Bellefonte. Operations continued through the turn of the century and the town peaked at around 500 residents.

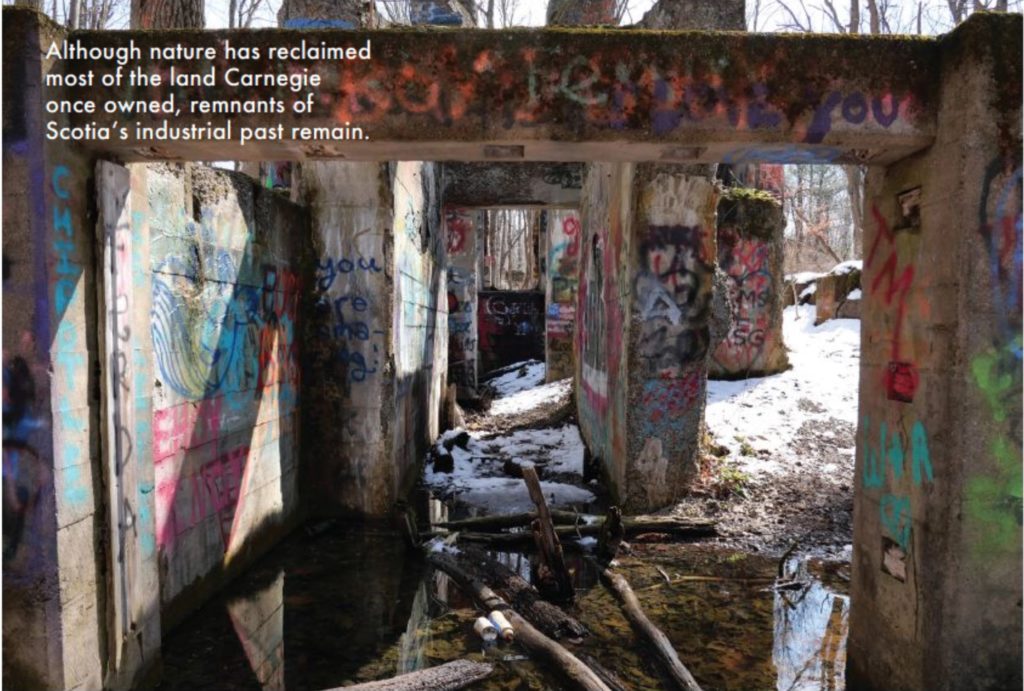

In 1911, the fortunes of Scotia ran out. The Bellefonte Furnace Company ceased operations in Scotia and soon after folded entirely, as it became cheaper to ship higher quality Minnesota ore into Bellefonte. By 1915, the Scotia line of the Bellefonte Central was closed, followed by the line from Tyrone several years later. The town was vacated entirely by the mid-1920s. As quickly as Scotia was established, it faded into history.

Today, Scotia can be explored through its many hiking trails. The adventurous hiker can wander in the footsteps of Andrew Carnegie and pass the ruined remnants of Scotia’s industrial past. The once-untouched wilderness has returned to nature. The age of iron has ended, leaving Scotia a memory of Centre County’s industrial past.

Local Historia is a passion for local history, community, and preservation. Its mission is to connect you with local history through engaging content and walking tours. Local Historia is owned by public historians Matt Maris and Dustin Elder, who co-author this column. For more, visit localhistoria.com.

This story appeared in the April 2022 issue of Town&Gown.

Sources:

Dubbs, P. M. (1971, January 11). Scotia Iron Town. Centre Daily Times, p. 15.

Hughes, M. (n.d.). A geologic wonder: Scotia Barrens: Pennsylvania center for the book. A Geologic Wonder: Scotia Barrens | Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Retrieved March 10, 2022, from https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/feature-articles/geologic-wonder-scotia-barrens