I had a unique plan for the evening of Saturday, Dec. 14. Lots of football fans would watch the televised Heisman Trophy presentation that night, but I would be viewing it with a former Penn State star who had placed second in Heisman voting many decades ago.

I happened to mention my plans to Steve, my 31-year old son who knows his fair share of Nittany Lion football trivia. But when I told him that I was going to watch the Heisman show with Richie Lucas, he surprised me with his response.

“Richie who?” Steve asked. Then, a few hours later, I was sipping coffee with a 27-year-old PSU grad student who loves all things Nittany. I wondered if the Lucas name would mean anything to him, but again I got a disappointing question: “Who’s that?”

So here I am, determined to fulfill my civic duty to Nittany Nation’s younger residents. I don’t mind if you Millennials roll your eyes and say, “Ok, Boomer.” Sure, I’m an old guy telling old stories, but I want you to know about the legendary Nittany Lion named Richie Lucas who achieved some remarkable feats:

-

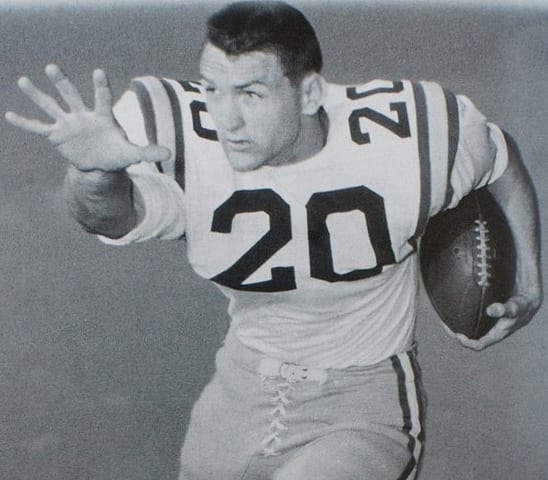

A three-year starter, Lucas came into his own in 1959, earning consensus All-American honors at the quarterback position.

-

The native of Glassport, Pa., set the single-season Penn State record for total offense that year, throwing for 913 yards and running for 325.

-

Lucas’ ascendance to greatness also helped to advance the career of Joe Paterno, then serving as Penn State’s quarterback coach.

-

Playing under the NCAA’s old rules that restricted substitutions, Lucas also played defensive back (he grabbed five interceptions in 1959 with 114 yards in interception returns) and punted 20 times for a 34-yard average.

-

Although Lucas finished second to LSU’s Billy Cannon in the 1959 Heisman race, he stands far above most Penn State stars with respect to the Heisman. Only running back John Cappelletti actually won the award (in 1973) while two others share second place finishes with Lucas: quarterback Chuck Fusina in 1978 and running back Ki-Jana Carter in 1994. Saquon Barkley? He finished fourth in the 2017 Heisman voting.

-

Lucas defeated Cannon to claim the 1959 Maxwell Award, an honor that is similar to the Heisman but brings a lot less national attention. (Joe Burrow won both the Heisman and the Maxwell this year.)

* * *

I felt honored to be in the presence of greatness while watching the Heisman telecast last Saturday night. Just three of us gathered to watch the trophy presentation: Lucas, me and our mutual friend, Patrick Funari, the son of one of Richie’s Penn State teammates.

The scene itself was nothing special. We sat in a lounge in one of State College’s assisted living facilities with a TV in front of us, a poinsettia plant to the left and a Christmas tree to the right. Richie sipped his ever-present Diet Coke while his walker was nearby, a sobering reminder of the damage that can be done by old football injuries and 81 years of aging.

But despite the ordinary setting, all of us realized that the occasion was notable for several reasons. First, this 2019 Heisman event marked the 60th anniversary of the 1959 gala where Lucas finished second. Yes, “only” second, but when I asked him why our society seems to be down on second-place finishes, Richie offered a word of wisdom.

“If you come in second,” he said, “I imagine it’s still a success. You’ve still beaten a lot of people out. But I don’t recall how I felt (at the 1959 award ceremony).”

Second, the identity of the 2019 recipient provided a special touch of significance. The winner, of course, was Burrow, and he became the first LSU Tiger to claim the Heisman since running back Billy Cannon beat Lucas for the honor in 1959. (Placing third in the ’59 vote was SMU’s Don Meredith who became famous as a Dallas Cowboy quarterback and as the “Dandy Don” sidekick for Howard Cosell on ABC’s “Monday Night Football.”)

Richie Lucas observes the 2019 Heisman Trophy selection show, 60 years after he finished second in Heisman voting. Photo by Bill Horlacher

EMOTIONS OF REGRET?

I wondered if the selection of another Tiger — and the resulting references to Billy Cannon during the telecast — would stir any “woulda, coulda, shoulda” emotions in Lucas. But no, not a chance. Watching Burrow struggle to control his feelings during the traditional winners’ speech, a sympathetic Richie said, “I was probably happy that I didn’t win it (the Heisman), because I would have had no idea what to say. I guess I was 21 years old, so that’s not easy. The guys who do it, you swear they must have been prompted.”

Even though Lucas had better stats than Cannon, the Tiger won the ’59 Heisman by a huge voting margin — 1,929 points to Lucas’ 613 and Meredith’s 286. No doubt, voters were in awe over Cannon’s unreal combination of speed and power, ingredients he demonstrated by breaking seven tackles on a game-winning punt return against Ole Miss. But the boy from Baton Rouge also was boosted by LSU’s team achievements—a national title in 1958 and a third place finish in 1959.

As for Lucas, he insists that he rarely thinks about his second place Heisman finish. Rather, he says that “winning the Maxwell was kind of nice since I’m from Pennsylvania and that was given in Philadelphia.”

LSU running back Billy Cannon won the 1959 Heisman Trophy, finishing ahead of Penn State quarterback Richie Lucas

BOOSTING STATE’S IMAGE

Even though Lucas fell short in the Heisman balloting, he played a huge role in helping to put his alma mater on the college football map. Keep in mind that the 1959 Lions followed four consecutive seasons of mediocrity marked by records of 5-4, 6-2-1, 6-3 and 6-3-1. And consider the fact that Penn State had NEVER won a bowl game as of the beginning of Lucas’ senior season. (The Nittany Lions lost to USC in the 1923 Rose Bowl and tied SMU in the 1948 Cotton Bowl).

Suddenly, the 1959 team began to deliver an atypical level of success, largely due to their dual threat quarterback. Penn State opened the season with seven straight wins, defeating teams that are still respected today (Missouri, Army, Illinois and West Virginia) and others who aren’t so highly regarded (VMI, Colgate and Boston University). But regardless of the opposition, “Riverboat Richie” was deadly on the rollout pass — electing to run or throw in response to choices made by defenders.

On November 9, the Syracuse Orange, ranked fourth nationally by the Associated Press, came to New Beaver Field to play Penn State, ranked seventh by the AP. “The Battle of the Unbeatens” attracted a record 34,000 fans to New Beaver Field, and the two teams staged a thrilling, toe-to-toe battle. Both teams scored three touchdowns, but the Nittany Lions missed an extra point kick and two attempts at two-point conversions. Syracuse’s 20-18 win helped catapult them to the national championship while Penn State finished with an 8-2 regular season after beating Holy Cross and losing to nemesis Pitt.

Penn State still had a chance to capture more national notoriety. Coach Rip Engle’s team accepted a bid to the Liberty Bowl, with a chance to battle 11th ranked Alabama, a rising power that was led by Bear Bryant, then in his second year of coaching his alma mater. Penn State triumphed, 7-0, but observers both northern and southern agreed that the Lions had dominated more than that score suggests. As for Lucas’ contribution, he ran the ball nine times for 54 yards and completed one pass for a gain of 23 — but then he was sidelined by a painful hip bruise in the second quarter.

The Lions’ first-ever bowl win pushed their season mark to 9-2 and gave them a final ranking of 10th in the Coaches’ Poll.

“I felt really good about the fact that we won,” says Lucas in reflecting back 60 years. “An Eastern team won a bowl game — that was unusual — and we beat Alabama.”

Richie Lucas watches 2019 winner Joe Burrow, the only LSU Tiger to win the Heisman since Billy Cannon won in 1959. Photo by Bill Horlacher

AFTER GRADUATION

As he left Penn State, Riverboat Richie beheld a bright future in professional football. He was selected by the Washington Redskins with the fourth pick in the first round of the 1960 NFL draft. But that was also the first year for the new American Football League, the upstart organization that later negotiated a merger with the NFL.

In order to lure graduating college stars, AFL teams offered various financial inducements, and among those who responded were Cannon (Houston Oilers) and Lucas (Buffalo Bills). But due to injuries, Lucas played just two disappointing years in Buffalo before leaving the professional ranks.

Buffalo’s loss, however, was Penn State’s gain. Lucas returned to Happy Valley and worked for a number of years in the athletic business office. Later he was promoted to assistant athletic director, a role he held until his retirement in 1998.

As an assistant A.D., one of Lucas’ key responsibilities was to oversee the coaches of various Penn State varsity teams. Included on his list was the wrestling team which was led by my friend, Rich Lorenzo, from 1978 to 1992. I asked Rich, owner of a 188-64-9 record during his years as a head coach, for his insights into Richie.

SUPPORTIVE OF COACHES

“He was the perfect athletic director for me,” said Lorenzo. “Richie was so supportive of us and the other teams he directed. He wanted to know what you needed — how to keep us on top and competitive on a national basis. But I think I must have given him some gray hair. He hired me and the first year we went 2-11. Richie would just say, ’I have faith in him.’”

And then I asked Lorenzo one more question about his former boss. Why has Richie Lucas, a second place Heisman finisher, become a nearly forgotten figure here in Happy Valley?

“That doesn’t surprise me,” responded the former Nittany Lion wrestler and coach. “If you really know Rich Lucas, you know he’s a very private person. He was very into his job, very supportive of Penn State athletes. He appreciated hard work, no matter what sport you were in or whether you were a coach or an athlete. He just wouldn’t get in front of a camera. He kept himself out of the public and out of the press. He’s amazing in the sense that he doesn’t want publicity. He’d just as soon have other people get it.”

So that’s the story of one of Penn State’s all-time football stars. Richie, I know you’re not looking for press clippings or TV notoriety, but I hope you won’t mind my attempt to share your career with the next generation. They need to know how Penn State took its place among the nation’s top teams. They need to know about people like you.