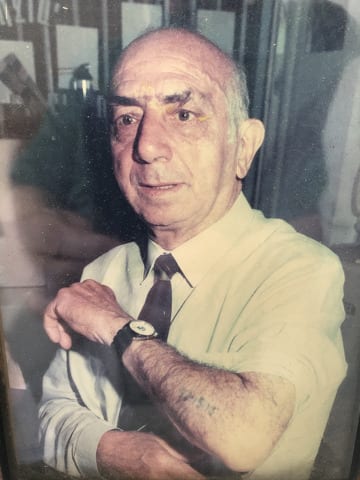

THESSALONIKI, Greece – A doctor examined Joseph Salem when he came home from Auschwitz in 1945.

He weighed 77 pounds. He was 29 years old. All five of his siblings had been killed. His parents also.

Nearly 50,000 Jews from Thessaloniki (also known as Salonica) – the entire Jewish population of the city minus the handfuls who hid in Athens or resisted in the mountains – were deported in 1943. Joseph Salem was among the fewer than 2,000 who made it back.

“You were born today,” the doctor told him. “Forget the past.”

Salem tried. He married Luisa Massoth, whose family had survived by obtaining forged identity cards. The couple had three children. Stella, the oldest, says she grew up in a family “with a lot of songs, a lot of laughs, a lot of love.”

As for the Holocaust: “It was a secret – as if it didn’t happen.”

One day, though, while she was still a child, Stella’s father took her to an exhibition titled, “You Cannot Kill a Picture.” The pictures were the artwork of children who died in the camps. “That woke me up,” Stella says.

Stella Salem got degrees in economics and law, taught the one and practiced the other. Eight years ago, at age 60, she embarked on a project that had its roots in the awakening she experienced at that long-ago exhibition. It’s called “The Lost Children of Salonica,” a two-volume work that lists the 12,000 Jewish children whose names the Nazis didn’t bother to record when they sent them straight from the cattle cars to the gas chamber.

Not only was the future of these children stolen, Stella tells me, but the future of Salonica itself.

“Children are the future of the city,” she says. “We can’t know how the city would be if these children had been here and could study, work, have families and be citizens of the community.”

English translations of the books are due out this spring.

Stella Salem is our landlady. When we let it be known that we intended to live in Thessaloniki for a year and would need a place to stay, our friends Rika and Kostas told us that Stella had an apartment with a terrace and a view of the sea. We jumped at it.

When I first heard her name I thought she sounded more like a pistol-packing rancher in an old western than a Greek Jew. Then I learned her last name isn’t pronounced like the Salem, Massachusetts, of witch trials fame, but that it rhymes with “ahem.”

Her family is one of the ones who settled in Thessaloniki more than 400 years ago when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella – Christopher Columbus’s patrons – kicked them out of Spain. The long, long tenure of the Jewish community here shouldn’t magnify the heinousness of the Nazis’ crimes, but somehow, it does. How could people who were so deeply rooted in a place be treated as interlopers who didn’t belong?

Last Sunday, Stella was among the Jews of Thessaloniki who gathered to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. A cantor sang Kaddish – the prayer for the dead. Dignitaries spoke: the mayor, the former mayor, the president of the Jewish community. Yossi Amrani, the Israeli ambassador to Greece, spoke movingly in English. The rest of the speeches were in Greek. I pricked up my ears when I heard “Pittsburgh” and “Poway” – the sites of synagogue shootings in 2018 and 2019.

Then survivors and diplomats laid wreaths at the base of the Holocaust memorial on the edge of the square where Jewish men had been tormented by the Nazis on a hot July day in 1942. Later there was a concert in one of the city’s two remaining synagogues (there had once been 19), the music so haunting it brought tears to my eyes.

As I walked home along the seafront that night, my affection for the city deepened. Despite or maybe because of a succession of historical catastrophes – fire, occupation, deportation, earthquake, economic depression – it is one of the most spirited places I’ve ever been.

Knowing that the city was shamefully slow to acknowledge the fate of its Jewish community (and the role of Greek collaborators), one could disparage the obliviousness of all the social energy one feels in the streets, in the cafes and along the water.

But when I saw how even the Jews were happily greeting each other on the somber occasion of Holocaust Remembrance Day, I thought of the Langston Hughes line, “Life is for the living/ Death is for the dead.”

The children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors aren’t in eternal mourning. They’re working, raising kids, socializing in the cafes like everyone else.

Stella herself was working on “The Lost Children” while making frequent trips to Athens and Tel Aviv to see her own sons and grandson. Her father died in 1995. Next month, because Joseph Salem came back from Auschwitz, his grandson in Athens is expecting twins.

*The headline of this column comes from the title of a collection of poems by the late Philip Levine, former Poet Laureate of the United States.

Russell Frank teaches journalism in Penn State’s Bellisario College of Communications. He is spending the 2019-2020 academic year as a Fulbright scholar in Thessaloniki, Greece.