“It is difficult to express in a few lines the value of General Hastings’ services and the kindly regard the people of Conemaugh Valley entertain toward him.” —Rev. David J. Beale, First Presbyterian Church, Johnstown

By the afternoon of Friday, May 31, 1889, record rains had already accumulated across Pennsylvania, with the worst being between Harrisburg and Johnstown. In Centre County, the waters rose in Elk Creek to dangerous levels, bursting about a half-dozen mill dams near Millheim and sweeping away sawmills, barns, horses, and pigs. The surging waters and debris from Elk and Pine creeks collided into Penns Creek at Coburn and swept away a home two miles east, drowning Mrs. Pfaust and her four children.

As heartbreaking as this is, it pales in comparison to the devastation in Johnstown, where the natural disaster was compounded by failure of the poorly maintained earthen dam at South Fork. Famed historian David McCullough quoted Pennsylvania Adjutant General Daniel Hastings describing the South Fork Dam as “criminal negligence.” Ninety-nine entire families were lost in Conemaugh Valley. According to the National Park Service, 2,209 men, women, and children perished, but the true death toll will never be known.

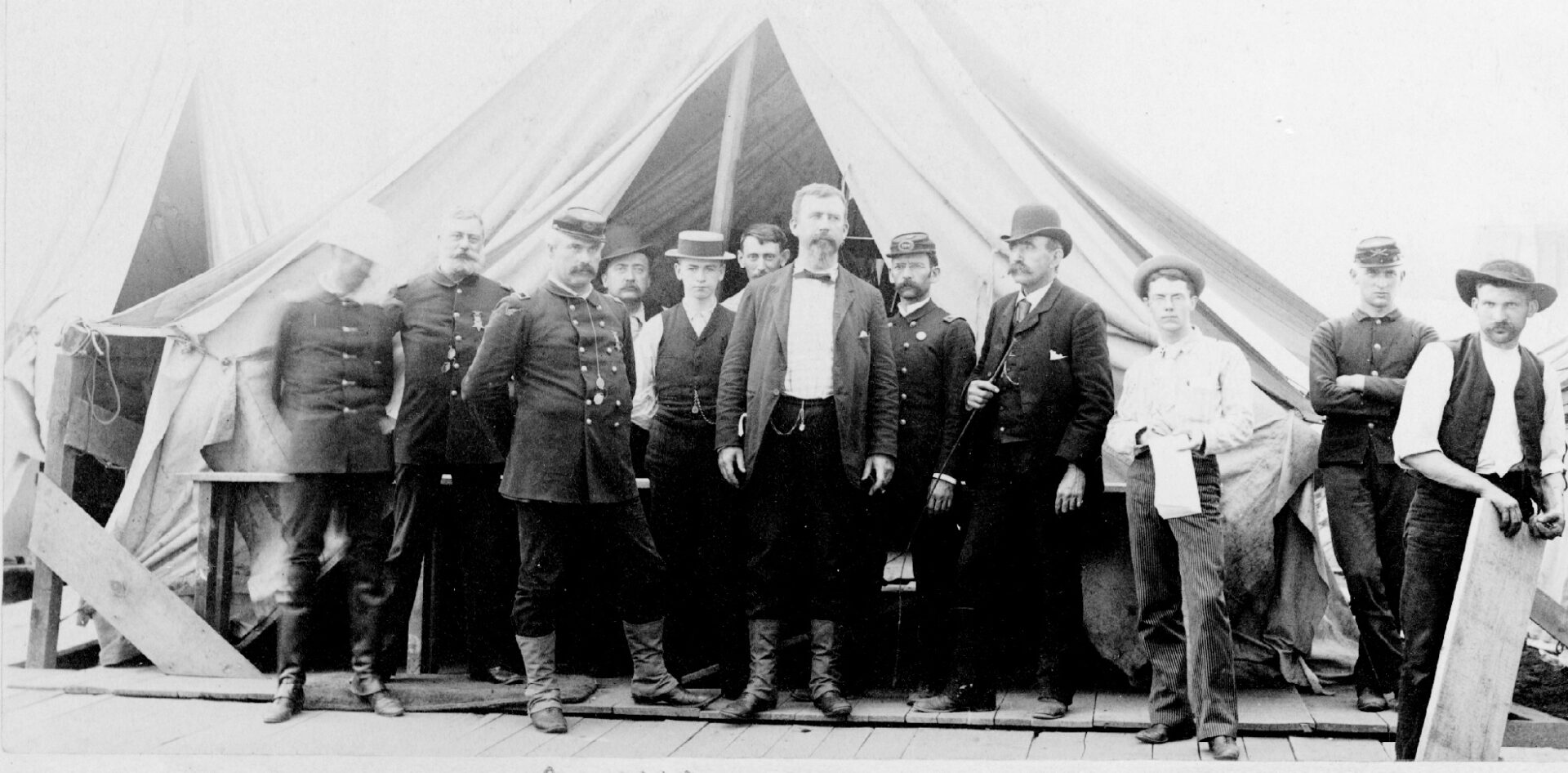

As the terrible news of “Black Friday” spread, Hastings—a resident of Bellefonte and future Pennsylvania governor—happened to be in nearby Cambria County tending to coal business and immediately hired a team and traveled with Colonel J.L. Spangler, also of Bellefonte, to Johnstown. Arriving on June 1, he was just in time to witness the horrible whirlpool of bodies and fires trapped against the stone bridge. According to Willis Johnson, author of the 1889 History of the Johnstown Flood, “General Hastings came here right after the flood, on the spur of the moment, and not in his official capacity. He rides his horse finely and looks every inch a soldier. He has established in his headquarters in the freight depot, a very much-needed bureau for the answering of telegrams.”

Hastings telegraphed Governor James Beaver for tents and supplies and soon after officially took over and “superintended all the attempts to aid the survivors and rescue the bodies of the drowned. He was placed in absolute charge of the work of relief for the flood sufferers and assumed the responsibility of taking under his control the dispensation of the stores and money that poured in upon the stricken city.”

Such leadership was characteristic of Hastings. As adjutant general under Governor Beaver since 1887, he didn’t wait for orders—just like when he was 13 years of age and tried to volunteer for the Union Army without his parents’ permission. He did not shy away from challenges and even became a Bellefonte principal at the age of 18. Although he missed the Civil War, Hastings rose through the ranks of the Pennsylvania National Guard. Up to that point, his only military experience had been in Altoona during the Great Railroad Strikes of 1877. Yet perhaps no one on earth was better suited to serve Johnstown in its time of need. Hastings would stay in Johnstown during the recovery for over a month until July 13, along with his wife, Jane Armstrong Rankin Hastings, who also aided in recovery efforts. Clara Barton, at Johnstown representing the Red Cross, described Hastings as a “gallant soldier [that] could not have been more courteous and kind.”

Along with the necessary repairs of railroads and bridges, sympathy and aid flooded back in for the “Johnstown sufferers”—building materials, clothing, food, gravediggers, train carloads of coffins, etc. Curious onlookers and amateur photographers were proving to be a nuisance, so Hastings required official passes and asked “railroads not to sell tickets to people to come to Johnstown unless they had a reason to be there.”

General Hastings came from a humble farm life in Salona, Clinton County. He managed to become a teacher, principal, lawyer, officer in the National Guard, adjutant general, and eventually governor of Pennsylvania. According to McCullough, “General Hastings would later be elected governor largely because of the name he had made for himself at Johnstown.” The local Grand Army of the Republic in Johnstown, comprised of veterans who had served the Union during the Civil War, even enrolled him as an honorary “comrade” for his service; his “beautiful badge of the order was set with diamonds.”The Johnstown flood is essential to understanding Daniel Hastings. Perhaps his right-hand man, Colonel Spangler, said it best: “The people of the State may hold you in high esteem for valuable public services rendered in your capacity as citizen, soldier, and statesman, but your clear head, generous nature, and kindly response to the demands of the distressed at Johnstown will be the brightest record and the best achievement you can ever hope to attain in this world, however exalted and noble your future station may be.” T&G

Local Historia is a passion for local history, community, and preservation. Its mission is to connect you with local history through engaging content and walking tours. Local Historia is owned by public historians Matt Maris and Dustin Elder, who co-author this column. For more, visit localhistoria.com.

Sources:

Beale, David J. Rev. Through the Johnstown Flood. Princeton: Edgewood Publishing Company, 1890. https://archive.org/details/throughjohnstown00beal/page/n9/mode/2up

“Former Governor Daniel H. Hastings is Dead.” Democratic Watchman (Bellefonte, PA), January 16, 1903. https://panewsarchive.psu.edu/lccn/sn83031981/1903-01-16/ed-1/seq-2/

Johnson, Willis Fletcher. History of the Johnstown Flood … with Full Accounts Also of the Destruction on the Susquehanna and Juniata Rivers, and the Bald Eagle Creek. Philadelphia: Edgewood Publishing Co., 1889. https://archive.org/details/historyofjohnsto01john/page/110/mode/2up?q=Hastings

McCullough, David. The Johnstown Flood. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 1968.

“The Flood! Great Destruction on Elk Creek.” Centre Reporter (Centre Hall, PA), June 6, 1889. https://panewsarchive.psu.edu/lccn/sn83032058/1889-06-06/ed-1/seq-4/

“The Great Storm of 1889.” Johnstown Area Heritage Association, 2013.